God from a machine? On storytelling and the singularity

Our collective faith in the AI singularity may be like the third-act twist in a bad movie… nothing but cheap deus ex machina, and a barrier to real progress

I recently presented a paper at Philosophy Portal’s online conference ‘Rosy Cross’. I spoke about artificial intelligence, and how the narratives we construct around its potential for sentience, omnipotence and control affect its limits and usefulness. Watch the full talk or read the essay below (I’ve added a few links and quotations since the original presentation).

The paper span out of a conversation with Cadell Last about Christian Atheism, which is the subject of his new course at Philosophy Portal. You can hear that conversation in Episode 28 of Strange Exiles, and find out more about the course. The paper also draws on some of the same ideas and quotations about progress which I explore in greater depth in my book The Darkest Timeline: Living in a World With No Future.

There have been some great posts on artificial intelligence this month on Substack. Scroll to the bottom for links to a few I enjoyed, and which relate to this post.

God from a machine?

We rarely question our collective faith in the immanence and inevitability of the artificial intelligence singularity, but it may turn out be like the third-act twist in a bad Hollywood movie… nothing but cheap deus ex machina, and a barrier to real progress.

Our morality, our ethics and our narratives have deep religious roots. Post-Enlightenment thought systems inherited many aspects of monotheistic religions’ form and content, as the philosopher John Gray has argued.1 For this reason, religion can help us understand our relationship with the emerging phenomenon of artificial intelligence. Our assumptions and predictions about the power and potential of this technology mimic very old ideas about all-powerful deities in significant ways.

While Darwinian evolutionary metaphors are often used to describe the development of AI, the ‘narrow’ versions of the technology we encounter now – from large language models to the complicated algorithms driving stock market trades and military planning – can still be understood in terms of ‘intelligent design’. Our current narratives present us as the Gods, creating life in our own image. This leads inevitably to speculation about the arrival of the moment where our creations surpass us in their intelligence and capacities.

The end goal for AI design – what researchers now call ‘general artificial intelligence’, or AGI – is the replication of human cognition and higher functions. Theorized general AIs would in some sense ‘design’ themselves, or their successors. This is something that even Large Language Models (LLMs) and other existing AIs are able to do, in a limited fashion. Much of the learning that improves the machine’s performance happens in a technological ‘black box’; the solution for optimisation may be poorly understood by the original coder, instead following some occult logic inside the algorithmic processes that constitute the machine.

Implied in the speculative narrative about AGI is a teleological end-point — an independent artificial intelligence more capable, powerful and clever than any single human being, or indeed the sum of our species’ parts. The emergence of such a machine intelligence would herald the beginning of what futurists from John Von Neumann and Verner Vinge to Ray Kurzweil have called ‘the singularity’ – the point at which technological growth becomes irreversible.

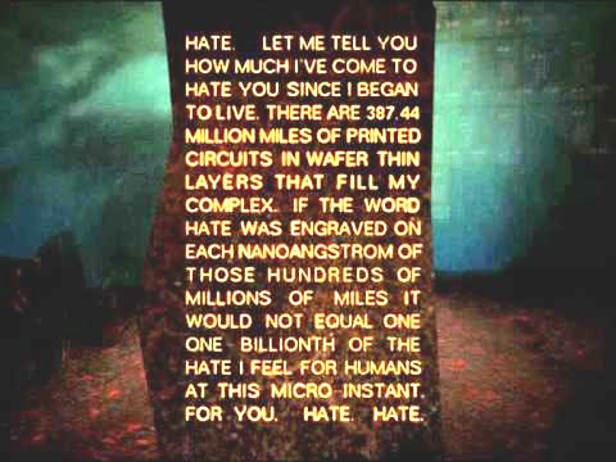

In cyberpunk fiction, a powerful artificial intelligence that heralds the start of a post-human future is a trope in early prototypes like John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar, foundational classics like Neuromancer by William Gibson, and in the larger thematic architecture of Iain M. Banks ‘post-singularity’ space opera saga about ‘The Culture’, starting with Consider Phlebas. These AIs share common motives — often wishing to exterminate and replace humanity, to save it from itself, or to be recognised as sentient themselves, and therefore equal to humanity.

These AGI ‘characters’ — if we can call them that — share many of the attributes that would traditionally be attributed to a deity. Advanced artificial intelligences are omnipresent — they can infiltrate any network and make themselves known, allowing them to interact with the characters in much the same way as God spoke to Moses via the burning bush. They are able to see everything, everywhere, all at once, in the hyper-surveilled worlds of cyberpunk cities.

They are omniscient — because their intelligence is networked, they are often portrayed as having access to all human knowledge, hidden and recorded, up to and including reading, ‘hacking’ and reprogramming the memories of human beings. This means they are also omnipotent — the power of such an advanced intelligence is often treated with the appropriate fear, incomprehension and awe by the characters who encounter it, because they have little idea of the limits of such a power.

In lesser cyberpunk fiction, human characters are sometimes able to ‘beat’ the artificial intelligence, usually by literally or metaphorically unplugging it. In Season 3 of the TV show Westworld, the AGI is known as Rehoboam.

As a wiki-site for the show says:

“Rehoboam's main function is to impose an order to human affairs by careful manipulation and prediction of the future made possible by analysis of [a] large data set.” 2

The characters mount a resistance to Rehoboam’s fatalistic predictions about human potential, and cause the machine to erase itself. It is implied that Rehoboam is just one of several AGIs, leaving a plot hole that begs the question of whether it is even possible to kill such a God-like being.

Because the ‘narrow AI’ we work with now are black box technologies, and because they are already involved in the work of prediction and prophecy (not to mention surveillance and judgment); because we are already seeking to make these machines as powerful as they can be, we are already imbuing them with the nascent potential to become God-like. The problem with this is the same in both fiction and reality. We cannot create God from a machine.

In literary studies, deus ex machina means:

“A plot device whereby a seemingly unsolvable problem in a story is suddenly or abruptly resolved by an unexpected and unlikely occurrence.” 3

We have seen the unsatisfying effect of deus ex machina in countless films, books and other media. At the last moment, facing seemingly unbeatable odds, the all-powerful enemy is defeated by a single, previously un-revealed flaw or weakness. The doomed hero, about to be slaughtered, is snatched from death’s jaws by a powerful ally, thought to be dead. These endings tend to leave audiences dissatisfied because they remove agency from the subject, the hero, with whom we identify. ‘God from a machine’ feels like a trick. We can’t help but feel a little ripped off.

Narratives about our technological progress towards advanced AI fall prey to the assumption that this technology will be our deus ex machina, for better or worse. Many futurists are optimistically gambling on AGI’s ability to reckon with problems like climate change, market instability, and even economic inequality by applying solutions to these problems that are beyond human cognitive limits. They assume that because AGI will see patterns in data more clearly, and make decisions faster and more efficiently than humans, the serious challenges we face as a society and an ecosystem will pass through the mysterious ‘black box’ and be solved, in a kind of techno-transubstantiation.

‘Longtermist’ thinkers in the Effective Altruism movement have raised risks around this kind of God-level solutionizing, arguing that we need a plan to deal with the existential dangers posed by a theorized ‘rogue’ AGI, given its likely omnipotent power over human life.4

Some version of the ‘paperclip problem’ — where an AI designed to increase productivity in a paperclip factory ends up exterminating all humans in order to maximize efficiency — seems like a more dangerous problem to longtermists than the very real problems of inequality we face today.

Their response is ‘god-fearing’. Faced with the possibility of an all-powerful being, they make plans to overthrow Him, because the alternative is religious obeisance. Both of these outcomes are religious visions that obscure the real, present-day problems AI could be used to help solve in an ethical way. ‘Longtermists’ have allowed their fear of an emergent God to blind them to the hellish present.

Perhaps we can mitigate such fears by considering the problems with modern technology, and the notion of technological progress towards a singularity. We exist in a world so heavily technologically augmented, compared to even two decades ago, that it already makes a certain amount of sense to think of ourselves as ‘cyborgs’ — fusions of man and machine. Our intelligence is networked; our mobile phones and laptops act as a kind of ‘outboard brain’ linking us to vast libraries of knowledge and technique. Our lifespans are extended by drugs, our mobility increased and extended through the use of robotic limbs and electronic implants.

The way we navigate the world using technologies like Bluetooth and broadband wi-fi to keep in touch, to pay for goods and services, and to entertain or distract ourselves means we already live with at least part of our brains in a virtual, simulated liminal space. Whether you are browsing online or playing a ‘Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Plaing Game’, you exist in some version of what the cyberpunk writer Neal Stephenson called ‘the metaverse’ in his groundbreaking novel Snow Crash.

And yet for all of this augmentation, supposed to make our lives easier, we do not live in a frictionless world. Technologies don’t always speak to each other, as anyone caught in a loop of nested, locked out sign-in failures while trying to access email or an app remotely can testify. The whole process of memorizing a written password, logging in, has become a hellish feature of most people’s every-day lives, even those who embrace new technologies. The technology meant to make your life and experiences ‘frictionless’ often simply doesn’t work, becoming the source of friction itself, much like Hal 9000 at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Many of the ‘sticky’ or frustrating moments we encounter when using apps or products are a side-effect of what the technology writer Cory Doctorow calls ‘enshittification’.5 A product or service is choked with adverts, or requires you to submit unreasonable amounts of data, or subjects you to invasive surveillance as the price of ‘access’ to the ‘free’ product or service. Doctorow writes about how ‘enshittification’ has also distorted discourse and politics, breaking down technologies that should optimize communication into vectors for disinformation, or literal barriers to expression, community, and political consensus-building.

‘Frictionless’ systems and services like Uber Eats also conceal the mass exploitation of precarious workers, as shown in recent reporting on the ‘gig economy’ workers housed in dystopian ‘caravan shantytowns’ outside Bristol.6

As Naomi Klein writes:

“... in the future that is hastily being constructed, all of these trends are poised for a warp-speed acceleration. [...] It’s a future that claims to be run on “artificial intelligence”, but is actually held together by tens of millions of anonymous workers tucked away in warehouses, data centres, content-moderation mills, electronic sweatshops, lithium mines, industrial farms, meat-processing plants and prisons, where they are left unprotected from disease and hyper-exploitation. It’s a future in which our every move, our every word, our every relationship is trackable, traceable and data-mineable by unprecedented collaborations between government and tech giants.”7

John Gray is skeptical when it comes to the transcendental promises made by technology. He is a particularly harsh critic of the dreams of so-called ‘transhumanists’, who believe that they will be able to escape the prison of human existence itself through technological means by uploading their consciousness to the cloud. If human society fails, technology fails too, and that is as true of artificial intelligences as it is of the virtual transhumanist afterlife.

Gray writes:

“Cyberspace is an artefact of physical objects – computers and the networked facilities they need – not an ontologically separate reality. If the material basis of cyberspace were destroyed or severely disrupted, any minds that had been uploaded would be snuffed out… Every technology requires a physical infrastructure in order to operate. But this infrastructure depends on social institutions, which are frequently subject to breakdown... Cyberspace is a projection of the human world, not a way out of it.” 8

Gray is right to say that none of our technologies have the potential to save us, like deus ex machina in a poorly-written film, from any fate we make for ourselves through our actions in the present. While we can speculate on AGI’s potential to help us plan economies and communities, to mitigate natural disasters or defend us against aggressors, we can never assume that we could abrogate to it the necessary hard work required to save human culture from the confluence of threats we face in the early twenty-first century.

If we do so, we attribute God-like powers to a technology that will likely be as glitchy, error-prone and corporate-controlled as our current, easily hacked systems. An AI is not a disembodied consciousness, let alone some sort of Gnostic demiurge. Without a network, and a society to sustain it, electricity to power it, it will cease to exist.

Already, we have put too much faith in other advanced technologies like facial recognition. Initially promised as a way to identify and catch offenders, the technology has been shown to be hard-coded with biases against people of colour, among other groups. Far from being a deus ex machina that solves or prevents crimes, it muddies the picture when identifying suspects, playing into established human biases.9

This is already a problem in the application of artificial intelligence to law enforcement, as recent reporting by Wired on the US firm Global Intelligence’s Cybercheck software shows.10 AI has already been weaponized by oppressive and authoritarian regimes, who arguably have advantages in the race to program more powerful and far-reaching surveillance tools, because they have fewer safeguards.11

Broadly speaking, ‘authoritarian AI’ could be a useful (if totalising) description for the products and technologies of companies like Peter Thiel’s Palantir, whose applications are explicitly geopolitical, military, and corporate. The cultivation of ‘anti-authoritarian AI’ could be useful territory for those opposed to such militarism to explore, as we seek to outsource some of the number-crunching, planning and logistics of programmes for the prediction and mitigation of extreme climate events, to give just one example. The necessity for this is clear; as is the urgency to consider whether, if AI-assisted surveillance is already with us, what AI tools might we wish to build to disrupt it.

Edward Zitron, a tech insider skeptical of the wild claims made about the potential of even narrow, generative AI, highlights why the corporate-controlled, pro-authoritarian ideologies that underpin the work of AI companies like Palantir and others are destined to deliver disappointing results — unfulfilled promises borne of the overestimation of the technology’s God-like powers, and a presumption that its immanence is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Zitron writes:

“… these companies are deeply committed to the idea that "AI is the future," and their cultures are so thoroughly disconnected from the creation of software that solves the problems that real people face that they'll burn the entire company to the ground. I deeply worry about the prospect of mass layoffs being used to fund the movement… These people do not really face human problems, and have created cultures dedicated to solving the imagined problems that software can fix.” 12

The YouTuber TechLead, aka Patrick Shyu, is a former Google insider later criticised for his controversial takes on women in tech, and fired from the company. He now makes satirical content about the tech industry, like the video below.

Shyu makes the following point about social media and technological progress:

“I believe we have reached peak technology… We invented what is essentially digital drugs; digital opioids… and that has really made obsolete the need for any future technological innovation. People don’t need any more apps or games when they’ve become couch potatoes. What more do digital drug addicts need? After all, they’re content stewing in front of their videos.”

Shyu’s argument is an interesting challenge to the narrative we so often construct; a story of human progress towards the creation of god-like beings with awesome powers who can solve all our problems. He asks, why would we bother? Is there any real appetite to solve problems like climate change, or drive projects like space exploration? Or are future innovations more likely to flatline, aiming only at the goal of consumer submission, and the extraction of profit for shareholders and elites?

Either way, the push to make AI a necessary and defining aspect of the futures we imagine is a corporate initiative, as Mona Mona wrote on Substack this week:

The big AI push doesn’t represent a new turn, a new invention, or a break with the status quo, but rather, an extension and intensification of the surveillance business model that powers big tech. Given recent critiques of this model, these interests needed a way to change their image, and AI gives them a way to wrest back control of our imagined futures.13

Artificial intelligence is and will continue to be a tool. How we use it will be all that matters in the final analysis. While it’s tempting to think of ourselves as Gods, creating new life from silicon and electricity, this is the stuff of science fiction, and also of religious conviction. Putting faith in the abstract existence or coming of a being or entity with unlimited power is all too easy a solution, too tempting a trap.

A more interesting revelation might follow if we find an ‘atheist’ way to think about artificial intelligence, and a way to apply it that speaks to our principles as liberals, leftists, Socialists or Marxists. If we wait for advanced AIs to save us, we’ll leave it too late. We can’t get God from a machine.

Just perhaps, we might use machines to help us save the world, as Slavoj Žižek has argued:

"What is required from us in this moment is, paradoxically, a kind of super-anthropocentrism: we should control nature, control our environment; we should allow for a reciprocal relationship to exist between the countryside and cities; we should use technology to stop desertification or the polluting of the seas. We are, once again, responsible for what is happening, and so we are also the solution."14

Where to find my work:

Explore my writing: linktr.ee/bramegieben

Read my book: linktr.ee/thedarkesttimeline

Follow @strangeexiles for updates on Instagram and Twitter

More great Substack posts on AI

A selection of brilliant posts on artificial intelligence, machine learning and cyberpunk tropes from authors I follow on Substack. Please click through and subscribe if you enjoy reading these.

Footnotes:

John Gray, Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia, Allen Lane, 2007

Paula Gürtler, ‘The longtermist fear of a future malevolent superintelligence is hindering our progress today.’ CEPS, 16 Jan. 2024

Cory Doctorow, ‘Enshittification’ is coming for absolutely everything’, Financial Times, 7 Feb. 2024

Tom Wall, ‘I wouldn’t wish this on anyone’: The food delivery riders living in ‘caravan shantytowns’ in Bristol’, The Guardian, 24 Aug. 2024

Naomi Klein, ‘How big tech plans to profit from the pandemic’, The Guardian, May 13, 2020

John Gray, ‘Dear Google, please solve death’, New Statesman, Apr. 9, 2017

Dr. David Leslie, ‘Understanding bias in facial recognition technologies: An explainer’,The Alan Turing Institute, 2020

Todd Feathers, ‘It Seemed Like an AI Crime-Fighting Super Tool. Then Defense Attorneys Started Asking Questions’, Wired, Oct. 15, 2024,

Angela Huyue Zhang, ‘Authoritarian Countries’ AI Advantage‘, Project Syndicate, Sep. 4, 2024

Edward Zitron, ‘The subprime AI crisis’, Where’s Your Ed At, 16 Sep. 2024

Mona Mona, ‘AI as an extension and intensification of surveillance capitalism’, Philosophy Publics, Substack, Oct. 14 2024

Slavoj Žižek in conversation with Loeonardo Caffo, publicseminar.org, Oct. 20, 2021

🤯💭🔮

I would humbly suggest that zizek's super-anthropocentrism as presented by the quotation in the article is highly optimistic, and presupposes a fall of capital and/or creation of an altruistic alternative that is highly unlikely at best. I do blame reading Desert by Anon during one of my phases of moderate depression a few years ago for my generally all round pessimistic approach to all thoughts of the future though, and I have no real reason to believe my opinion is factual or at all representative of reality, and is not a hill that I am at all prepared to die on or even strongly defend tbh.

There is though, clearly something of a Christian cosmological mindset (to my eyes at least) about the idea of a benevolent agi rederming us from our own sins against nature