Aleš Kot: The Only Constant Is Change

Aleš Kot is one of the last true renegades of comics. Psychedelic, violent and savagely clever, his work is critically acclaimed, and his place in the comics pantheon assured. We spoke in 2012...

Photo: Ales Kot by Clayton Cubitt. This interview was originally published on Mishka NYC’s Bloglin in 2012.

Aleš Kot's graphic novel Wild Children, published by Image Comics in 2012, was a delicious metafictional confection. It took scientific theories about the multiverse, and pumps them full of ideological rocket fuel, fusing the anti-authoritarian politics of Lindsay Anderson’s IF…. and updating it for the twenty-first century.

A group of the eponymous 'wild children' take over their school. Their dialogue, the narrative and panel borders bristle with elliptical quotations from the likes of Bjork, Ian Bogost and Hakim Bey. Ales Kot's first graphic novel arrived fully-formed; a bastion of a new, densely literate and allusive type of comics; marrying complex, high-art notions and minimal, Situationist drama.

Kot grew up reading the work of the first wave of The ‘British invasion’ comisc writers like Grant Morrison and Alan Moore, and explored some of the same meme-pools they fish in, in both Wild Children and his other early works. In every comic he has written since, he has proved himself to be the first comics creator to absorb, process and evolve these ideas for a new generation of readers.

USA Today called Wild Children: “Network for the prep school set,” and it's not a bad comparison – Kot's comic shares a sense of societal outrage, of a driving need for change, with Sidney Lumet's 1976 film. He wears his influences on his sleeve, and has always synthesised them in a way that is urgent, visceral and unique.

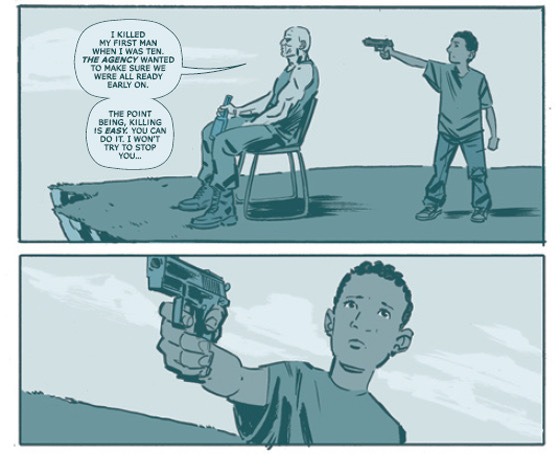

Panel from Zero. Art by Tradd Moore.

Aleš and I spoke in late 2012 following the release of his second major work, Zero, a sprawling spy thriller with a sinister, fractured, paranoid twist that defies logical (or spoiler-free) explanation. It would go on to run for four highly acclaimed volumes. He was also on the verge of releasing two more one-shots that would go on to define his singular style.

Enjoy this wide-ranging discussion about his work, his influences, and the very start of his meteoric rise through the ranks of comics creators.

“Comics are unique as an art form because they give readers complete control over time and space in which they appear.”

Change takes place in a fictional Los Angeles which revolves at an 'odd angle' through time, and sees Kot channel themes of cosmic horror from Lovecraft, and the high Californian weirdness of Philip K. Dick.

The Surface, meanwhile, is a cyberpunk surveillance adventure with strong metaphysical leanings, and a sort of meta-sequel to Wild Children. Kot’s mercurial, research-intensive, high-concept subject matter is laced tightly into the worlds and characters he creates. His panels are packed with references to music, net culture and futurism.

Kot got into comics at a young age: “I was about four and very sick, and my parents brought me a comic book - Donald Duck, that kind of stuff,” he says. “I started reading and I forgot I was sick. Then, a few years later, my grandfather, who used to be a truck driver, brought me comics from some abandoned factory he was clearing out. The Stern/Romita Spider-Man era, Conan the Barbarian, the late 70's Marvel stuff, mostly. It blew my mind again.”

A moment of spectacular violence in Zero. Art by Matt Taylor.

“I made a few of my own comics, for example this mash-up of Street Fighter, Batman and True Lies that got really weird because the main character had a pig head. I was about seven, I think. I continued reading comics, but I haven't had an idea that I wanted to make them and be serious about it until late 2008. I was seriously considering killing myself at the time and I thought: 'Maybe I should try doing something that will really make me creatively happy first, and if it doesn't work out, I can always kill myself later.' So I sat down and started learning and writing.”

Kot quotes Alan Moore's thoughts on comics, and what they can achieve as an art form: “Rather than seizing upon the superficial similarities between comics and films or comics and books in the hope that some of the respectability of those media will rub off on us, wouldn’t it be more constructive to focus our attention upon those ideas where comics are special and unique? Rather than dwelling upon film techniques that comics can duplicate, shouldn’t we perhaps consider comic techniques that films can’t duplicate?”

“I want people to feel incredible things when they look at the comics I make... I want to help people be more alive.”

Asked how he applies this in his own work, Kot embarks on an epic explanation: “I'm interested in whatever is the most effective way to communicate whatever it is I want to say. Comics are unique as an art form because they give readers complete control over time and space in which they appear. We can flip through a comic book in a minute or spend an hour reading it. We can read just the first panel on every page and string together something deeply meaningful. We can just look at the images and not read the words. There are so many ways to read comics, so many ways to ignite our imaginations through them.”

His sense of the ‘physics’ of a comics page develops ideas found in Grant Morroson’s experimental panel explosions in works like We3 and The Filth: “The empty space between two panels is where we fill in the blanks - it's where we participate on a level that's quite uncanny. We finish the story in our own mind. We develop it. No two readings will ever be completely identical. The amount of information we can convey through words and pictures on one page can be quite something. And words are also pictures, technically speaking.”

A page from Zero shows the technical precision of Kot’s writing, even where there is no dialogue or captions…

For Kot, Moore's axiom that language and magic are the same thing finds a particularly powerful expression in comics: “It's all sigils,” he explains. “The way we put them on paper influences reality. When we create a new work, whether it's a new comic book or painting or film or performance art or whatnot, we present new information and new ways to process information. Being a creator is a social function, and it's a tremendous responsibility.”

This notion of comics as a unique and fascinating way of playing with time and space is given space to breathe in Change: “We're playing with information density quite a bit,” says Kot. “It's quite unusual these days to get something like twenty panels on one page and I think it shouldn't be. I look at someone like Guido Crepax or Michael DeForge and I marvel at how much information one page can deliver. Now, combining the density of panels with density of text and increasing complexity is a game I'm currently into. It's a theme that plays directly into our current narrative as human beings and I'm interested in what's happening now.”

Looking back on this interview after a few years have passed, it’s striking how much emphasis Kot places on the reader’s experience, and the primacy of joy in the experience of reading, despite his complex, often dark subject matter: “I want people to feel incredible things when they look at the comics I make, I want people to feel incredible things when they read them. I want to help people be more alive. I like the idea of increasing empathy and making the world a better place. Now, that can be achieved through a vast variety of stories - not just the ones with good endings or stereotypical three-act exercises.”

And of course, when working with an artist like Change's Morgan Jeske, a writer's imagination is literally unbounded, in terms of what it can seek to create: “I love being able to have an unlimited budget when it comes to creating the images and getting them on paper,” says Kot gleefully. “Comics allow me to do that and extract the images from my head with the help of my collaborators. They're fast and they're cheap.”

“Separation into 2D and 3D is a work of fiction in itself.”

Change is a comic that dealt, in a very real sense, with the fallout of an approaching singularity. It's a challenge that Kot said in 2012 that he and Jeske were “doing our best to pull off.” The resulting graphic novel stands the test of time, more than messuring up to the brief Kot set himself; to describe “...the fracturing of space and time that is happening to so many people - synchronicities abound, sacred geometries become strikingly visible. The similarities between each one of us and their implications can be quite haunting, transcending time and space.”

This exploration of time and space is at the heart of why Kot loves writing comics: “What better medium to explore them in if not the medium that allows you to control both?”

Change is also about Kot's experience of living in Los Angeles. “I moved to Los Angeles in 2009 to be with my girlfriend, then wife, now soon-to-be-ex-wife,” says Kot. Did he love the place instantly? “My first reaction to LA was - while still on the plane and walking through LAX - 'Holy shit, I'm in Heat.' I always loved that film. It transcended fiction for me. The way Mann depicts the city, that cool detached sense of space that is still absolutely connected to the inherent melancholy and dreaminess that Los Angeles has in spades - I felt all that. The air was electric and full of possibilities, and not just because of the myths and because I was in love. It was real.”

A few days later, Kot had another reaction: “'It smells like hell, but it looks worse.'” His descripton of the city is characteristically poetic: “I climb on the roof of our then-apartment in Hollywood, above the transsexual hookers and drug dealers and Armenian mothers and old Italian guys with cigars and palm trees, and I look at the city, and I see the mountains and the ocean and the slums and the skyscrapers and the roads and the highways and the mansions, and the homeless and the SUVs and the supermarkets and the parking lots and the paper billboards and the digital billboards and the sand, and I smell the wind and look at the vast blue sky with almost no clouds, and I realize I'm home.”

Born in the Czech Republic, he moved around schools a great deal when he was young; part of the inspiration for Wild Children. Kot has gotten used to a somewhat nomadic existence. “I do carry my home within me - I am my own home,” he says. “But there's a connection to Los Angeles that I'm just beginning to unravel and I have no idea how long it will take. I love this city because it has everything. This is where the reality meets up with the dream and they fuck until they can't breathe, so they just rest on each other breathless and merging until you can't tell which is which.”

Change is in part a time-travel story. How did Kot avoid the pitfalls and plot-holes of this often treacherous fictional ground? “My approach could be called 'Shoot first and let the universe and my hard work sort it out,'” he says. “We all time travel every time we imagine or recall our pasts and futures. I'm travelling into my own past to influence my present, in a sense, trusting my own conscious / subconscious / unconscious autopilot to lead me where I need to go.”

As with Kot's other work, the thinking of Carl Jung was a big influence: “Change is ridiculously Jungian,” he says. “I came up with the - relatively simple - story skeleton, started developing it, then made ten steps back and looked at the entire thing from far away, dissecting it in relation to my own psyche. And oh, the implications.”

Zero was already enough to moisten the palms of any comics fan, or indeed any James Bond afficionado, before the deeply weird left turns it took in subsequent volumes. For all its weirdness, it stayed rooted in Cold War spy fiction. What attracted Kot to the genre? ”I always loved it,” he says. “The spy thriller genre and the super-spy thriller are tonally different, but they often deal with a lot of the same themes - glorification of white crime, politics of power, gender politics... oh, we also get fights, chases and beautiful women.” Kot would go on to write James Bond himself for Dynamite Comics - a testament to how influential his mind-melting approach to espionage proved.

The character was the hook that got him writing: “In the beginning, I was simply enamored with the ideal of the extremely capable man who does what he wants and gets what he came for, but as I grew older and discovered more about the world we all live in, I started realizing that figures like Andrew Zero are not nearly as cool as they might have seemed. Zero is a thug first and foremost. He's easy to steer as long as you give him a decent target, enough booze and painkillers and some women on the side. He's the bleak male force unleashed.”

It's a subtle mashup – given that the spy thriller and super-spy thriller are close cousins, what will make the character of Edward Zero different from a Bond? For Kot, it's about the questions the character poses: “How do you live with being a person like Edward Zero? You're young, you're great at killing people, you're an addict... where do you go from that? Do you even go anywhere? What if you begin questioning what you're told by your superiors? Answering those questions will take us all over the globe.”

The theme of generational trauma haunts Zero, and much of Kot’s work. Art by Michael Walsh.

In The Surface, Kot would end up addressing complex notions about the nature of reality and consciousness, as he did in Wild Children. “The way I describe The Surface is 'What if Moebius worked on District 9 or Inception?' I'm not saying we'll be reaching his greatness, but we are certainly doing our best to deliver the strongest, most interesting comic book we can possibly create, with a strong imaginative bent,” Kot told me at the time.

“I like making stories because I like giving people a chance to feel and think in new ways. With The Surface, that love for imagination translates into the environment of the comic in a very direct way, because we enter a place people considered an urban myth for decades - a place that allows us to transform it with our minds.”

The plot is deceptively simple: “Three hacker kids on the run. One place away from everything, or so it seems. What can go wrong? Pretty much everything.” Kot promises the work will explore not only the complex theories of 'Ideaspace' and virtual realities, but deep psychological territory as well.

It's this mixture of psychological exploration / excavation and fabulistic near-future SF that would become Aleš Kot's trademark, along with a sharp, sardonic wit and surreal sense of humour. He dives into what could be incredibly dry, intellectual territory with a light, easy touch and an assured grip on character and structure. The Surface asks interesting questions: “How about the nature of our reality, for starters,” begins Kot enthusiastically. “Are gigantic robots fun? And what are the bonobos doing there?”

Returning to his breakthrough comic, Wild Childen, Kot is completely upfront about the way he uses quotations, homages and references in his work. “Whatever works, works,” he says. “It's as simple as that. Does it work within the story, does it feel new because of the connections you have created? If so, use whatever you want. Be nice, be inventive, never settle for a half-assed decision. Create the most truthful story you can come up with.”

He talks of the “deep influence” he “felt from many different areas.” It was a question of using his influences wisely to help him grow and evolve: “I understood that I wasn't as good or elegant writer as I wanted to be and I couldn't simply transcend the influence certain creators had on me yet, so I decided that the only way out was through - owning up to the influences and embracing them, finding the good in them.” He pulls it off with remarkable flair. “I tend to be pretty holistic about life,” he says, “so it wasn't that hard to achieve.”

One theme that has emerged in Kot's work is the notion of comics 'universes' as a stable alternative dimension - how far does he take this notion, in terms of applying it to his own life, and his approach to reality? “3D is just 1D away from 2D,” says Kot wickedly. “Life is a string of moments that we put together, separated so often within every second that we can't measure the frequency according to which the empty space between two moments appears. That empty space is to our life in 3D what the gutter is to comics, which are two-dimensional. That empty space contains every possibility. That empty space - every single one of them, however many there are for every second - is where we can transform ourselves and the universe. It is beyond dimensions and beyond words. The thing is, that separation into 2D, 3D and such... is a work of fiction in itself.”

Asked to explain the flecks of ink in the panels and margins of Wild Children, he attributes their presence to: “Punk rock aesthetics, pure and simple. A way to transfer raw energy on the page without diluting it.” Music is one of the passions Kot explores in his work – who were the bands he loved first, and where have his tastes led him lately? “I really enjoyed Backstreet Boys when I was about ten,” says Kot. “How's that for being controversial? Shortly after: Prodigy (Fat of the Land being the first thing I ever heard from them), The Cure, Pink Floyd. Then Radiohead, The Velvet Underground, Tori Amos, Venetian Snares, UNKLE and many others. I was about fifteen and exploding. So much good new music. It beautifully deformed me. Recently: Johnny Greenwood's scores for There Will be Blood and The Master are works of art. The new Bat for Lashes album. Mutamassik. The Notorious B.I.G., Marnie Stern, the new remix album Bjork just put out... Reign of Terror by Sleigh Bells has some great pop songs. I love Talking Heads more and more with every day. Godspeed You! Black Emperor's Alellujah! Don't Bend! Ascend! fascinates me to no end. Anything Ben Frost touches..” Just like his comics work, Kot's playlist is a thick gumbo of influences and flavours – there's a little bit of everything in there. Perhaps it shouldn't work, but it does.

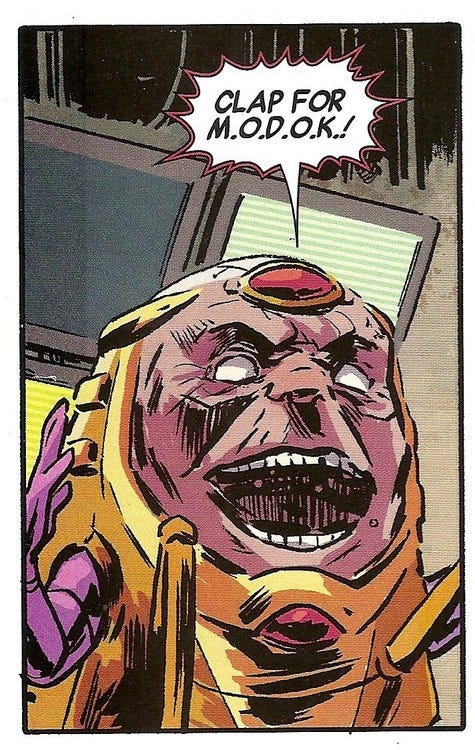

Although the great majority of his work before and since this interview has been creator-owned, Kot went on to write justly celebrated runs on mainstream titles like Secret Avengers (his demented take on MODOK is essential reading), Suicide Squad and The Winter Soldier, bringing his vision and several incredible artists with him to the spandex-clad big leagues.

Probably my favourite MODOK panel ever, from Kot’s Secret Avengers run. Art by Michael Walsh.

At the time, this was still in his future, just another branching timeline in the indinite multiverse: “Superheroes are very interesting and I get how they work,” says Kot. “I would be flattered to be asked and I would certainly consider it. Can I tell the story I want to tell while honouring the character and the character's history? If the answer is yes, the company is interested and we agree on the terms, I'll gladly do it.” It was, they agreed, and he did… and the comics world got a little bit weirder.

I finished up the interview with one final question. Given that his work is so densely packed with research, can he explain just how he became so goddamned clever? “My parents taught me to read early on,” Kot replies. “I read books and comics by the time I was three years old. When I was ten, my favorite writers were Stephen King, Terry Pratchett, Clive Barker and Neil Gaiman. Looking at my life right now, I think that explains a lot.”