Episode 13: The Darkest Timeline

Explore the aesthetics of the apocalypse and take a walk through the ruins of progress as we draw near to cascading catastrophic colony collapse.

Thanks for coming back to join us for Season 2 of Strange Exiles.

Episode 13 was a walk through the darkest timeline, looking at the aesthetics of the apocalypse in the works of John Gray, William Gibson, Slavoj Žižek, Adam Curtis and others.

We’re all living closer to the End Times than ever before, but as William Gibson tells us, the event horizon of apocalypse is not always visible. It depends where you stand. If you’re lucky enough to live far from the predations of climate collapse, crushing poverty or civil unrest, then please use this handy apocalypse generator to provide some context.

It’s easy to imagine the end of the world… what if we did the other thing?

Reading recommendations from the Darkest Timeline

“The future is already here - it’s just not evenly distributed.”

- William Gibson, quoted in The Economist, 2003

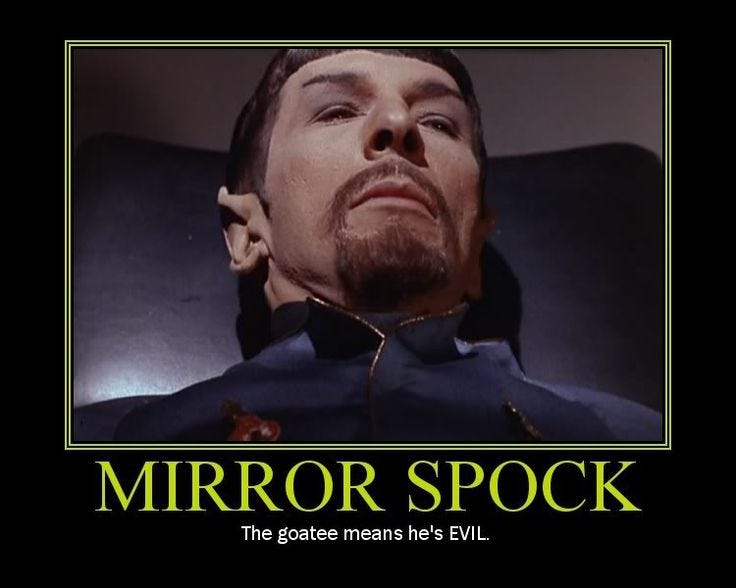

The Darkest Timeline is a Community joke that I have long adopted as a kind of totem. If our timeline is not the darkest, then whatever is transmitted into my brain to come out as essays or poetry or fiction must come from a very dark place. Of course, the main reason I know I am not from the darkest timeline, or indeed the mirror universe, is that my facial hair is not remotely villainous enough.

Before diving into this episode’s recommendations, let me point you at an excellent collection of essays on the subject of apocalypse. I didn’t read Katie Goh’s The End, from 404 Ink until after I recorded this episode, but the regions it explores (in greater depth) are similar. Goh’s analysis of the aesthetics and history of apocalyptic film and fiction are incisive and incendiary. This is a collection that packs a phenomenal number of ideas into a small page-count, and I highly recommend it.

Gavin Jacobson, writing for New Statesman on Mark Fisher’s appreciation for Children of Men, touches on points I mentioned in the episode. The realism of Alfonso Cuarón’s dystopia is a contrast to the decades of dystopia-lite and YA dystopia that would follow. And yet, the grimy, grey pre-apocalypse it presents is also a cliche now. There seems to be no apocalypse left with the power to shock or appall.

Hard Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, by Haruki Murakami is one of the strangest pieces of cyberpunk ever produced. The 1985 novel distils a fear of the digital future with an almost magical realist aesthetic, to produce something un-nerving and weird. The quotation “Everyone, deep in their hearts, is waiting for the end of the world to come” is from another Murakami novel, IQ84, which explores a millenarian cult.

Writing about the “relentlessly uneven and contradictory character” of capitalism in 1985, the great sociologist and cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s analysis of inequality and injustice is among the most intelligent and eloquent produced. His ‘Selected Political Writings’ is one of the foundations of modern thinking about race, capital and society, in particular under Thatcherism.

William Gibson is the godfather of cyberpunk fiction and to this day a writer of plausible dystopias - they just get closer and closer to the present. You can read the full 2003 interview in which he said: “The future is already here – it’s just not evenly distributed.” A lot of the content of which still rings true nearly two decades on. I also quoted from his excellent novel Pattern Recognition:

“Things can change so abruptly, so violently, so profoundly, that futures like our grandparents' have insufficient 'now' to stand on. We have no future because our present is too volatile...."

I found a copy of the short speech given by US President Jimmy Carter at the Voyager Probe’s 1977 launch - it really does offer a potent glimpse into the psychology of 1960s liberals, who would go on to become the neoliberal policy hawks of the 1980s and 90s, with statements like: “We human beings are still divided into nation states, but these states are rapidly becoming a single global civilisation.” If indeed we do one day go on to “join a community of galactic civilisations,” as Carter hoped, we can only speculate about whether that will be in the guise of colonisers, or profiteers. It’s unlikely to be as idealists, sad as that is for the dreams of men like Carter.

There are a few good articles about Denis Villeneuve’s austere, empty take on Blade Runner: IndieWire has a piece on its’ climate change aesthetics, and I greatly enjoyed Daniel Boscaljon’s exploration of the virtual in the film. If you got the impression I didn’t like Villeneuve’s work, you’re mistaken - I find its coldness intriguing. I also think his work is shallow; able to mimic depth through its austere minimalism. As such, it’s a rich seam for textual analysis, and he’s a film-maker I’ll no doubt return to again.

“Capitalism cannot imagine a future beyond itself that isn’t utter butchery.”

This is a quote from a 2020 essay on apocalyptic fiction (or “catastrophe porn”, a brilliant phrase) by the journalist and author Laurie Penny. Her fervent, partisan writing always gets my blood going - her latest book Sexual Revolution: Modern Fascism and the Feminist Fightback is on my reading list. Even when I disagree with her arguments (which is often), her writing is powerful, and always relevant. We need more writers like Laurie Penny in the world.

"The past is fucking prologue."

- Roger Stone, quoted in Politico, 2019

I talked a little about how and why this became one of my mantras, and why I always feel its is acceptable to champion or celebrate great writing, great sayings, or great ideas, no matter whether they come from a ‘problematic’ individual or source. This is one of my most deeply-held principles, and I intend to explore it in a little more depth on an upcoming episode.

I’d place problematic individuals like Stone in the same class as the likes of Charles Manson, Ted Kaczynski, or Valerie Solanas, all of whom I have quoted before on the podcast - they are outliers. Unlike these three however, Stone is (or has been) a powerful man, with unparalleled influence and sway. How an individual’s power relations affect the way their speech is received, and can be used, is an interesting question I also hope to explore.

I covered Jordan Peterson, Joseph Campbell and the hero’s journey in Episode 8, and the newsletter, so won’t add much here other than to say that his latest outing with human sternocleidomastoid Joe Rogan is like listening to two divorced dads shit-talking about the collapse of morality.

If you want worse examples of the two poles of toxic masculinity - brazen and unwarranted confidence, and weepy self-pity - you’ll struggle to find them. I say this as someone who can neither completely dismiss Peterson, and who enjoys Rogan's contrarian bullshit, even when he’s jUsT aSkInG qUeStIoNs. Separately, neither can be dismissed. Together, they reinforce each others’ worst aspects.

The section of the episode on the documentarian Adam Curtis span out from this 2021 VICE interview, in which he talks about modernity, and his approach to film. If you’re not familiar with his documentaries, they are nearly all available on YouTube, and there isn’t a single bad one. The channel JustAdamCurtis has several. In particular, The Century of the Self, Hypernormalisation, and All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace are thought-provoking analyses of the twenty-first century’s historical and cultural roots.

The big ideas from Episode 13 nearly all come from Mark Fisher or John Gray. I’m never done trying to sell you a used copy of Capitalist Realism, and I’ve recommended Gray’s seminal text Straw Dogs before. This 2017 New Statesman piece covers some of Gray’s approaches to transhumanism and technology. On the same topic, I quoted this piece by Antonella Dibiase, from Motherboard:

“Even post-humanism, assuming that we reach it one day, will remain marked by the economic rationality which currently dominates."

Dibiase’s essay is an excellent and provocative read for anyone with even a trace of techno-optimism. The same goes for Doug Rushkoff’s 2018 piece, which sees him blow the lid on the cynical technocratic philosophy of venture capitalists, for whom Rushkoff acted as a consultant futurist. You should also get involved with Rushkoff’s excellent podcast Team Human, which served as a bit of an inspiration for Strange Exiles.

For more on Slavoj Žižek’s latest position on anthropocentrism and climate change, read his 2021 interview with Publicseminar. For his earlier position, I’ll recommend two of my favourites of his books, 2010’s Living In The End Times, and 2018’s Like A Thief In Broad Daylight. These two constitute some of his most prescient writing on post-capitalism, and its current impossibility.

I quoted a 2017 essay by Jason Hinckel and Martin Kirk on Fast Company: "Either we evolve into a future beyond capitalism, or we won’t have a future at all." This is a good essay to send to anyone who believes that some form of ‘ethical’ or ‘well-managed’ capitalism will solve climate change and address inequality.

Finally, if you want to put all this doom and gloom in perspective, have a read of Natalie Wolchover’s 2017 essay for Wired, which covers biophysicist Jeremy England’s theories on the origin of life. We’re nothing, we come from nothing… and we consume everything in our paths.

Coming up in Season 2…

This was another pretty personal episode, I hope you enjoyed listening. Season 2’s off to a start, and there will be more solo episodes as we go. I’ll soon be announcing a few upcoming guests. Thanks, as always, for your support.

Disagree with my pessimistic take in Episode 13? Let me know in the comments! I’m fascinated to hear from anyone who can find hope or optimism in these times, and against these arguments. There’s nothing more satisfying than a pessimistic theory or argument disproved or countered.

Believe it or not, I do entertain hope. I hope that I’m wrong.

Until next time…

Subscribe at sptfy.com/strangeexiles

Follow @strangeexiles for updates

All subscribe links anchor.fm/strangeexiles

Take care of each other.

Bram E Gieben, Glasgow, April 2022