Episode 14: Katie Goh - Interrogating the Apocalypse

Author of an acclaimed book on apocalypse fiction, writer and critic Katie Goh shares her thoughts on The End Times, and where we go from here

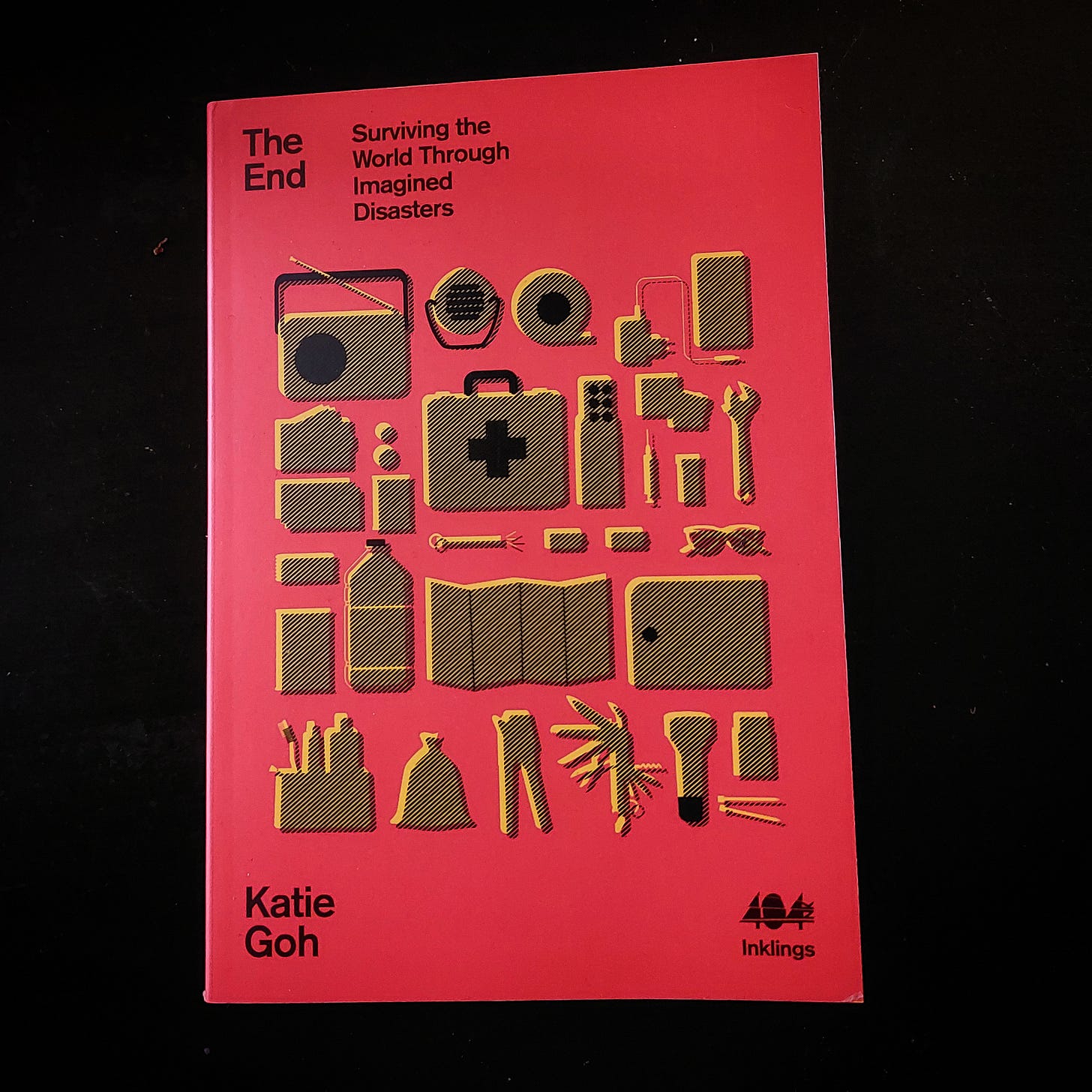

Welcome back to Strange Exiles! Our first guest in Season 2 is critic and journalist Katie Goh, the author of the book The End: Surviving the World Through Imagined Disasters. We discuss representations of the apocalypse in fiction, film and culture at large. Listen here if you haven’t had a chance yet.

Below, you’ll find some reading and watching recommendations based on our conversation. It’s brilliant to have Season 2 properly underway after an unexpected break, so thanks again for sticking with us. If you’re new to the show, welcome aboard - I hope you enjoy the ride.

Recommendations from Katie Goh

I really enjoyed this conversation with Katie, not least because she had a positive, optimistic outlook on some of the themes, ideas and texts I explored in Episode 13. It’s both provocative and inspiring for me to encounter a different take on issues around societal and environmental collapse, and I really value the ways in which Katie’s analysis re-interprets the often negative conclusions drawn by critics of dystopian fiction.

We covered a lot of ground in the show. Below, you’ll find a list, in no particular order, of the stories we talked about, plus a few of the critical theories that influenced Katie’s arguments. Before that, here are a few places where you can find her writing online.

Lots of links to Katie’s writing can be found on her website katiegoh.co.uk. A great place to start is her original essay on apocalypse narratives, for The Skinny. A few other highlights I really enjoyed are a sharp piece on opinion journalism and identity (also for The Skinny), and one on an important repository of lesbian culture and activist history, Glasgow Women’s Library (for Dazed).

In terms of Katie’s writing on film, her re-appreciation of American Psycho (for Girls On Top) is excellent. Her piece on the importance of diversity in film criticism, for The Skinny, makes a convincing argument for greater representation in critical spaces. Her pop culture analysis (see her piece on Taylor Swift and the ‘lonely girl era’ for i-D) is just as incisive as her directly political journalism (see her piece on ‘buffer zones’ and anti-choice protests in the UK for gal-dem).

Katie’s fantastic book on apocalypse narratives and aesthetics is part of 404 Ink’s innovative nonfiction ‘Inklings’ series, which features some brilliant writing by the likes of James Coe and Arusa Qureshi (among others). Katie is also an editor and contributor at gal-dem, where she commissions new writing from diverse voices.

She mentions an early essay on the confessional ‘I’ in poetry in the work of Sylvia Plath (and beyond). An astute argument for the function and importance of the first-person singular in poetic voice, this is a strand she continues to develop in her work as an editor for the poetry magazine Extra Teeth. I found this a really interesting analysis, especially where it ran counter to my own opinions on poetry and voice (something I can maybe expand upon in an essay in future).

The films, TV and books Katie and I discussed were nearly all from her book, and include several of the classic, key texts from popular dystopian fiction. We talked about The Hunger Games (2012), and the use of the three-finger salute in Hong Kong pro-democracy protests. We spent a fair bit of time on ‘climate disaster’ films, including Armageddon (1998), San Andreas (2015) and The Day After Tomorrow (2004), with a brief shout-out for Sharknado (2013).

We discussed the film of Annihilation (2018), and Katie went into more detail about her admiration for the original books, Jeff Vandermeer’s Southern Reach Trilogy (2014, FSG). In discussing the breakdown and collapse of nature in Vandermeer’s work, we talked about Philip K. Dick a little bit. The novels I was thinking of but did not reference directly were Martian Time Slip (1964), Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said (1974), and UBIK (1969), each of which turn on the idea of a reality that slips, dissolves or decays in some way.

The J.G. Ballard novels Katie mentions in her book are The Drowned World (1962), and The Crystal World (1966), both of which she cites as early and excellent examples of climate fiction. The former deals with a ‘flooded world’ scenario not too different from what we might now see in a standard YA fiction post-apocalypse; the latter is much weirder, telling the tale of an expedition into a forest devolving through time as it is consumed by mysterious crystals. It’s definitely a prototypical influence on the later work of Vandermeer, and all five of these novels are among my favourite SF stories.

One film I wish I’d asked Katie for her take on is A Boy and His Dog (1975), an offbeat and darkly ironic take on the ‘white male at the end of the world’ trope from a script by Harlan Ellison. We unpacked the archetypes of the ‘lone survivor’ and ‘doomsday prepper’ a little bit, touching on The Walking Dead (2010 - present).

We discussed one of Katie’s favourite kinds of dystopia, which she calls the ‘workplace apocalypse’. This ties directly into her argument that dystopias are a prime vector for deconstructing capitalist realism, with which I wholeheartedly agree. In particular, we discussed the excellent and unsettling TV show Severance (2022 - present), but also Ling Ma’s book of the same name (Severance, 2018, FSG), which offers a zombie-based story of alienated labour.

In discussing the role of the critic, and how social media has affected professional criticism, we touched on Stranger Things (2016 - present), Game of Thrones (2011 - 2019) and House of the Dragon (2022 - present). I attempted to make the point that often, media outlets will commission both positive and negative criticism of the same programme or film (witness the Guardian’s glowing praise and somewhat sneering review of the new ‘Thrones prequel), towards positioning the viewer as the final critic and arbiter.

Katie also mentioned some of the foundational classics of dystopian and apocalyptic fiction, such as H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898, Heinemann), and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985, McLelland & Stewart). For Katie, the latter was a powerful early influence, speaking to her as an allegory for the struggle for abortion rights in Ireland. This Guardian piece on the history of the abortion rights debate there has an overview of the real-world timeline.

For me, some of the power of Katie’s analysis is down to the tradition it embodies and seeks to evolve - namely, the analysis of pop culture to understand ideas, identity and ideology. Katie cites our old pals Mark Fisher and Slavoj Žižek in her book, and her analysis of disaster fiction offers similarly provocative and revealing insights into familiar works. She mentioned a graduate website run by Edinburgh University that encouraged and published Fisher-esque critiques of pop culture - I’ve struggled to find this, but Fisher’s approach has its roots in his revered 2000s culture blog k-punk (which saw a comprehensive printed collection by Repeater in 2018). For aspiring cultural critics, it’s become something of a style bible, and a continuing source of inspiration.

Katie also mentions Postcapitalist Desire (Repeater, 2021) which is the only Fisher book I haven’t read - that’s going in the wishlist. Katie’s writing put me in the mind of Fisher’s classic The Weird and The Eerie (2016, Repeater), which we mentioned in the episode too. I love this mode of analysis, and am really happy to see its continuing development through the work of Katie and others. It’s a powerful tool for understanding complex ideas.

In an interview with Charlie Rose, Žižek unpacks his analysis of Kung Fu Panda (it also appears in at least one of his books, if I recall correctly). It’s a great example of the way even the most disposable works can be used to unpack difficult ideas. Žižek remains one of my favourite writers on film - his texts are ferociously dense in places, but the excellent 2006 documentary The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema is a brilliant introduction to his particular mode of cultural and political analysis of pop culture. The sequel to Sophie Fiennes’ original film, The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, is just as good (if not better).

I’m currently working my way through one of the key texts by Frederic Jameson, a literary critic to whom both Fisher and Žižek are indebted (particularly for the idea that ‘it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism’), and in which tradition Katie’s writing sits comfortably. In The Political Unconscious (1981, Cornell Press), Jameson sets out an argument for understanding history through the Marxist analysis of literature and other art forms. It’s heavy going, but I am starting to see how the ideas and approaches developed in Jameson’s work provide a framework for the generation of cultural critics that would later follow Fisher. The film criticism over at The Quietus offers some tremendous example of this tradition and style.

I briefly mentioned the concept of ‘secular heresy’ first found in John Gray’s Straw Dogs. It underpins his arguments against the notion of progress, which he applies to various topics in his pieces for The Guardian and other places. As I’ve written here before, I believe Gray is one of today’s key sceptical and rational thinkers, and always worth reading, even when you disagree with him.

Finally, we talked about the phenomenon of artists editing their work post-release due to fan demands. I alluded to the story of activist Hannah Diviney, whose interventions on social media caused both Lizzo and Beyoncé to remove ableist language from their lyrics. The Guardian republished a piece by Diviney on the Beyoncé lyric back in August of 2022. Katie also mentioned the kerfuffle around samples on the Beyoncé album Renaissance, which was also edited post-release. This phenomenon isn’t going away any time soon - just last week, a Taylor Swift video was re-edited after accusations of ‘fatphobia’ from social media critics and fans. For now at least, popular calls for artists to ‘do better’ seem to be having an effect.

Next time on Strange Exiles: John Barnes

Our next guest is a writer I have wanted to interview for more than a decade. I’m very excited to share our conversation with you. John Barnes is the author of more than thirty works of immaculately researched, vividly imagined alternate history and speculative fiction. Winner of a Hugo Award and multiple Nebulas, his contribution to the ‘cyberpunk’ genre is as vital as that of William Gibson or Bruce Sterling, and just as prescient, predicting (with frightening accuracy) trends in climate science, technology and politics. He has co-written with the astronaut Buzz Aldrin, and possesses a vast knowledge of everything from computer science and data analysis to the history of theatre.

Come back in a week or so for a brand new essay on Barnes’ 1995 book Kaleidoscope Century. The novel made a powerful impression on me in the early 2000s with its themes of shadow governments, outsourced espionage, memetic warfare and technological singularity.

Episode 15 will be available everywhere you listen to podcasts from 23 November, 2022. Until then, find me at the links below!

Subscribe at sptfy.com/strangeexiles

Follow @strangeexiles for updates

All subscribe links at anchor.fm/strangeexiles

Take care of each other.

Bram E. Gieben, Glasgow, October 2022