Episode 19: Brett Gregory - Labyrinths of Austerity

Writer-director Brett Gregory on his bleak, moving, semi-autobiographical film, which tackles austerity, class, and mental health

Episode 19 is an interview with Brett Gregory, writer and director of the award-winning film ‘Nobody Loves You and You Don’t Deserve to Exist’.

Content warning:

This episode features discussions of suicide and self-harm. Brett and I discuss his bleak, brutal, starkly beautiful film, which has won more than 50 awards on the festival circuit, including the Workers Unite Film Festival in New York, and The Capri Hollywood International Film Festival in Italy. It was recently covered by the UK leftwing press, winning praise from Jacobin and Prospect Magazine.

We explore the film's themes of austerity, poverty, the high cost of living, and the wreckage they have brought to the lives and mental health of so many in the UK. You can currently watch the film on Amazon and on Apple TV. You don’t need to have seen it to get something from the episode, but it will definitely be worth your while.

Special thanks to the film’s producer Jack Clarke, who joins us for the interview, and helped make it happen.

This month’s newsletter is a guest blog by Brett, who follows up our conversation with some more thoughts on the process of making his film, and the very personal stories of deprivation and alienation which make up its rich thematic tapestry.

‘How to be angry, how to tell stories…’

Brett Gregory on his influences and origins

Although I was born on an RAF base in Buckinghamshire I was raised on a run-down council estate in a Nottinghamshire mining town from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s.

After my alcoholic stepdad was arrested for assault for the umpteenth time, my mum became a single parent on benefits with three children. We had no money: we ate salad cream sandwiches, we used the local newspaper as toilet roll and I could only afford to go to the cinema once over this period of time, and that was to watch ‘Tron’ at the ABC Cinema in 1982 for my 11th birthday.

Every other movie I watched was either on a black and white portable television in my bedroom or on pirated VHS tapes on the colour television in the living room downstairs.

As a result, I have no spiritual affinity with cinema-going or any of its mystical rituals like many other filmmakers claim to have. With television however it’s a different story.

For example, in 1982 I also grew aware of the power of the British State by following Newsnight reports about the Falklands Conflict throughout the spring. This was far removed from reading about World War I or World War II in history books; this was seemingly happening in the present tense right before my very eyes.

It was around this time as well when I became fascinated by a puzzle book called ‘Masquerade’. The author, Kit Williams, had buried a bejewelled golden pendant in the shape of a hare somewhere in England, and in the book – which told the story of Jack Hare – he’d hidden textual and pictorial clues in order to pinpoint the pendant’s exact location. I never solved the puzzle, and the treasure was discovered by way of fraud in 1988. The 2009 BBC documentary ‘The Man Behind The Masquerade’ tells the story.

In 1984 the Miner’s Strike broke out and, as hundreds of working-class communities were torn apart across the Midlands and the North, I then became aware that the British State would attack its own citizens just as readily as it would foreign entities. Watch video footage of ‘The Battle of Orgreave’ online and you’ll see what I mean.

Such familicidal tendencies were further demonstrated in the mid-1980s when Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government launched a completely unhinged and homophobic public health campaign using the slogan: ‘AIDS: Don't Die of Ignorance’ which infected an entire generation of adolescents with paranoia, distrust and self-doubt. The original leaflet is archived by the Wellcome Trust.

Surrounded by all this new knowledge and real life horror, it’s no surprise that by this point I’d started to read Stephen King novels and Clive Barker’s ‘Books of Blood’. In turn, I’d also begun to take the family’s Jack Russell, Shandy, on three hour long walks across farmers’ fields and to a nearby forest, as faraway from civilisation as possible.

Obviously I wasn’t a monk however, and would lead a double life by hanging around the front of the shops on the estate with older teenage lads in the evening: learning how to smoke, how to spit, how to swear, how to be angry and how to tell stories ‘that had better be fucking funny!’

When everyone eventually wandered home I’d then return to my bedroom and switch on the Acorn Electron personal computer which my mum had bought on hire purchase to keep me quiet.

Interestingly, if you wanted to play ‘free’ DIY games like ‘Tomb Hunter’ or ‘Spy Raider’ on a personal computer you had to type in hundreds of lines of BASIC code which were published in magazines like ‘Electron User’. However, if you made one single error – missed out a number or a letter, or typed a colon instead of a semi-colon – then the game wouldn’t work.

Little did I know at the time but this painstaking transcription process taught me extremely close reading skills and these would later prove very useful when I studied literary theory and literary criticism as a part of my BA and MA degrees in English Literature in the 1990s and, in turn, when I began to write, direct and edit short films in the 2000s.

In 1988, while writing a crappy ‘Twilight Zone’-style short story on a second-hand Olivetti typewriter in the kitchen, I noticed that Thatcher’s Tory government had now begun to mute all television broadcasts that featured representatives of Sinn Féin, a practice that would only end in 1994. It was at this very moment when it was confirmed for me that I didn’t live in a free society, and I probably never had.

Why was I was being denied access to this information? Why was I being denied the opportunity to make up my own mind about things, or gauge how I felt about such things? Or consider how I should or should not react to them? Or even learn from them? Furthermore, what other information was being withheld from me? What else didn’t I know? And why?

Naturally, as a young man desperate for answers which he was never going to receive, I grew frustrated and started searching out alternatives to the mainstream like I was on some sort of survival mission. I began to read the work of ‘troublemakers’ like George Orwell, Edgar Allen Poe, Jack Kerouac and Oscar Wilde, as well as whatever biographies I could lay my hands on at the local library in town.

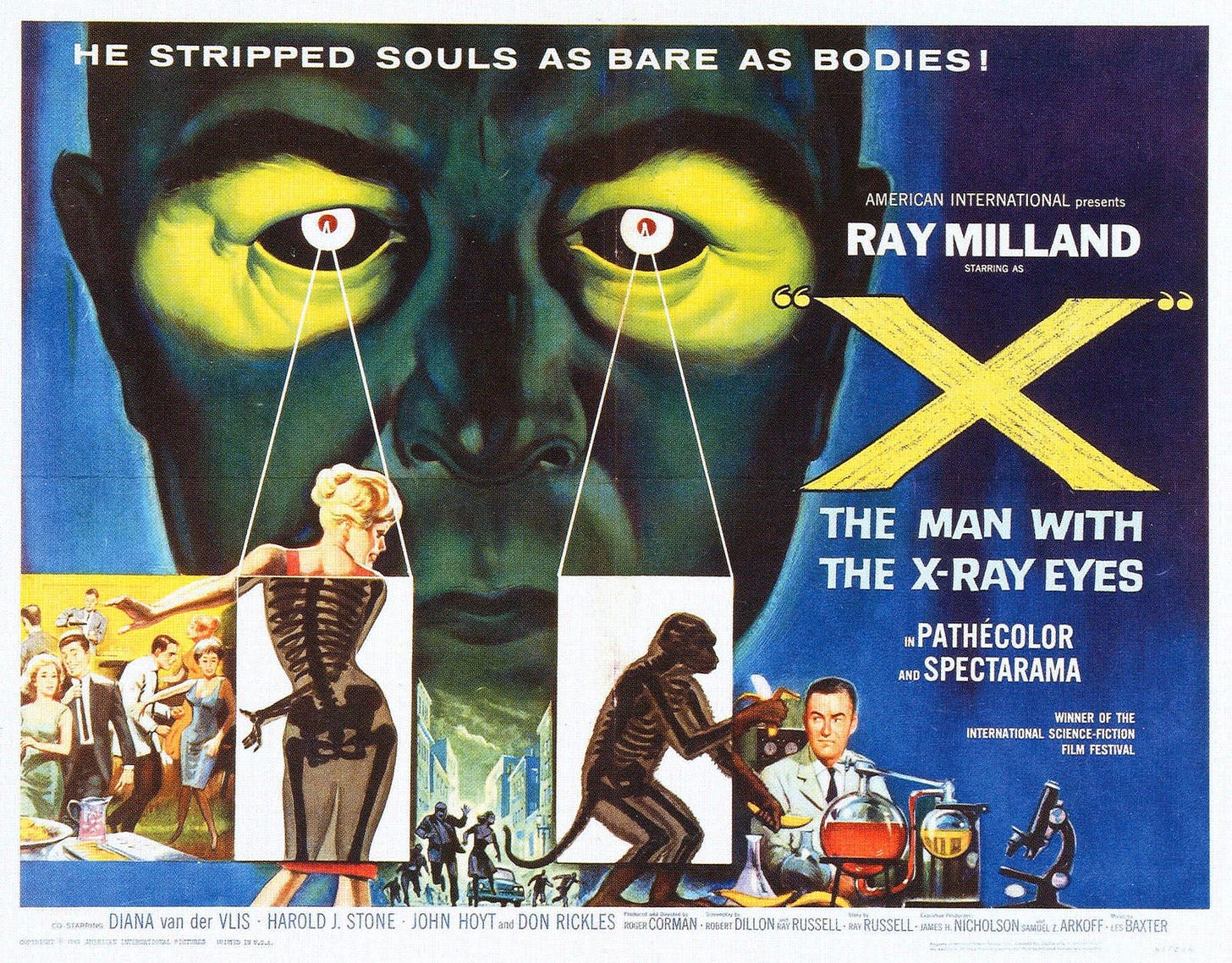

In turn, I also started watching Moviedrome on BBC 2. A late night television series which started in 1988, it was basically film school for poor people. Subversive film director Alex Cox (‘Repo Man’, ‘Sid and Nancy’) was the presenter. He would enthusiastically discuss the origin, production, style and themes of films which I’d never heard of. These films would then be screened and I’d suddenly feel my imagination expand, feeling a little less insane and a little less alone. Science fiction classics like ‘X: The Man with X-Ray Eyes’, ‘The Incredible Shrinking Man’ or ‘The Fly’ (with Vincent Price), and newer experimental fare like ‘The Man Who Fell to Earth’. Rugged 1970s films like ‘Five Easy Pieces’, ‘Point Blank’, ‘Badlands’ and ‘The Parallax View’.

What this four year study programme of ‘cult’ films taught me, as well as the literary books I was now rifling through on a regular basis, was that it wasn’t simply what you thought that mattered but, if you desired to feel vaguely like yourself on your own terms, then how you thought was just as necessary.

After finishing my BA and MA about eight years later I started claiming housing benefit for this damp, solitary bedsit I was confined to while I worked part-time at the library at the University of Derby for the next six years. The main reason for this was so I could have free access to all the books which I’d never had the opportunity to read while in formal education. I gorged myself on Jorge Luis Borges, Dante Alighieri, Leo Tolstoy, Charles Bukowski, Gustav Meyrink, Jean Genet, Umberto Eco, James Joyce, Knut Hamsun, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Primo Levi, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Alasdair Gray and Franz Kafka.

After watching the attacks on the World Trade Centre on television on September 11, 2001, I realised that the human race and its leaders were never going to improve during my lifetime, and so I decided I might as well study to be a teacher, sharing what I’d learned, before it was too late. In 2003 I then managed to secure a job teaching A Level Film Studies and A Level Cultural Studies at a college in Manchester.

These recollections of my early personal and cultural life form the basis of my aesthetic approach in ‘Nobody Loves You and You Don’t Deserve to Exist’. For example, as well as the myth of Sisyphus and Hieronymus Bosch’s ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’, the narrative structure is loosely based on Virginia Woolf’s ‘To The Lighthouse’, and the Lacanian phallocentric ‘I’ - which is associated with this novel’s subtext. In the film, Young Jack even points to the Stoodley Pike monument at one stage and exclaims, “And that big tower looks like a lighthouse, dunnit?”

In turn, different types of storytelling are addressed in an effort to try and understand how and why these represent, and even help to construct, who we think we are. For example, there are also numerous ‘storytellers’ present throughout, but who is telling the truth? What about gossip, rumour, poor memory or falsehoods? Who should we trust? The dominant third-person narrator; the newsreaders on the mobile phone; Boris Johnson; the Granny’s voicemails; the female interviewees’ recollections; the protagonist as a boy, as a youth or as a man; Brett Gregory the screenwriter or Brett Gregory the director?

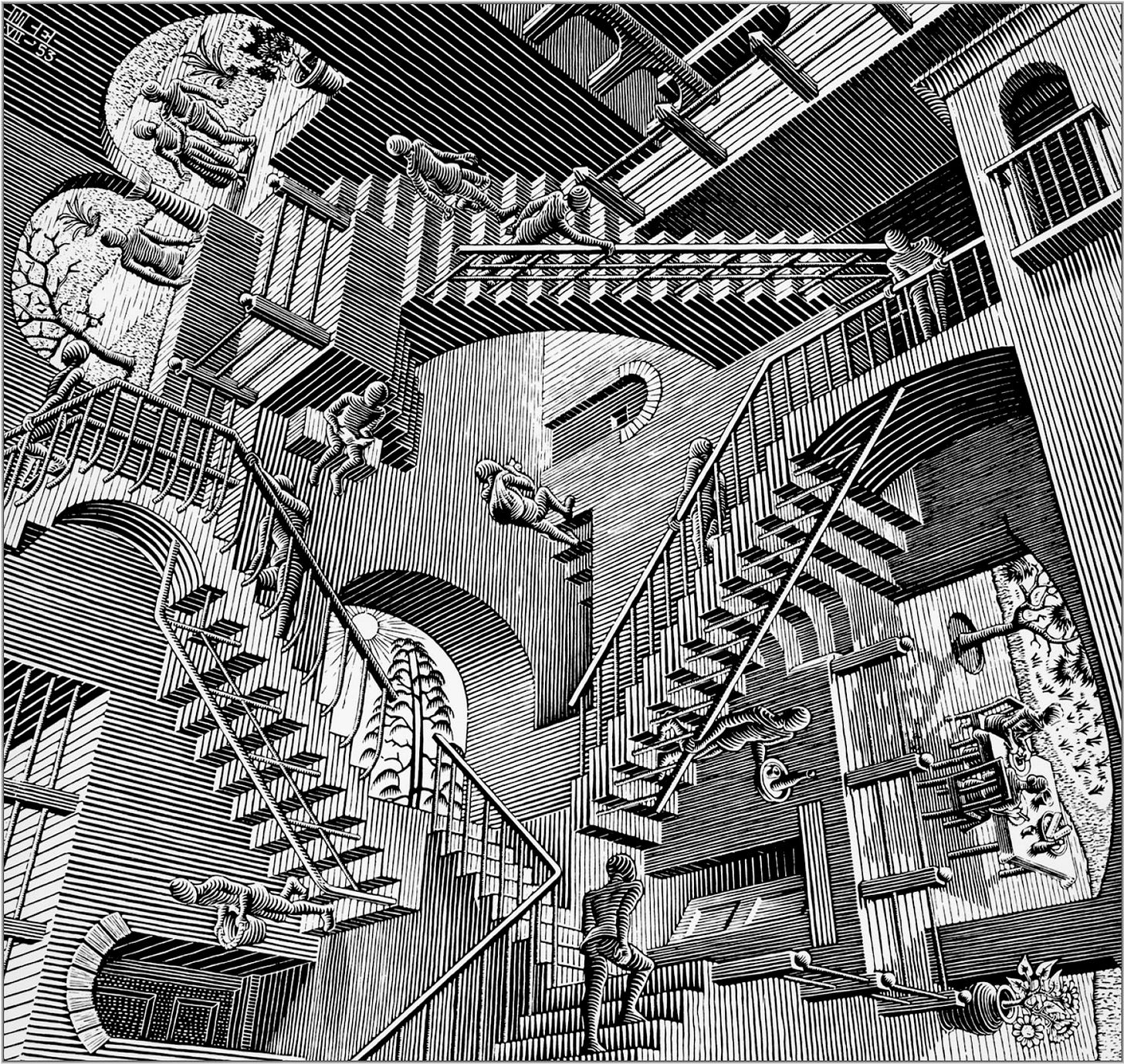

A copy of Kit Williams’ ‘Masquerade’ appears in one of the opening scenes as an intertextual prompt. The characters Young Jack, Jack and Old Jack each tell the audience that they’re looking for their missing dog, Shandy, who keeps getting lost while chasing rabbits. So all three ‘Jacks’ are chasing an invisible ‘Jack’ Russell who, in turn, is chasing the fictional ‘Jack’ Hare from ‘Masquerade’ in the hope that this will ultimately lead to… what? Treasure? The Truth? The Prelapsarian Past? This idea of losing oneself within oneself is also flagged up in the opening Borges’ quote from ‘Labyrinths’, and reiterated in the print of M.C. Escher’s ‘Relativity’ which appears on one of the doors in the protagonist’s flat.

The monologues delivered throughout were written to function as the characters’ streams-of-consciousness, rather than spoken words, since what they’re saying and how they’re saying it is far too complicated to be deemed to be a part of the social realist genre.

In these ways then the film is structured like a working-class modernist novella and, I suppose, this is why a general audience finds it difficult to understand. If my name was David Lynch and/or the film had been distributed and marketed by A24 I presume people would be inclined to put more effort in.

This said, I have great faith that the film will find a wider audience over time. Co-producer, Jack Clarke, who’s around twenty-five years younger than me, has promised to make sure the film is still available to audiences long after I’m gone.

Brett Gregory, June 2023

Thank you very much to Brett for his guest post, and for sharing his story with such honesty and courage. Thanks to everyone following, listening to and sharing the podcast, as always.

The next couple of episodes might take a bit longer, so thanks in advance for your patience. I’ll make an announcement soon about who our next guest will be.

I’ll see you all in a few weeks. Until then, take care of each other.

Subscribe to the podcast at sptfy.com/strangeexiles

Follow @strangeexiles for updates