Maximum Rez: Cyberpunk classics

A selection from the genre Fredric Jameson called the "supreme literary expression if not of postmodernism, then of late capitalism itself."

In my new book The Darkest Timeline I make the case that cyberpunk is the only truly culturally relevant form of science fiction in the 21st century. I argue it’s both a horizon that subsequent SF writers have struggled to transcend, and still a prescient and useful critical system for understanding and analysing our present state of technologically-accelerated hypercapitalism. I agree with Fredric Jameson’s pronouncement that cyberpunk is the "supreme literary expression if not of postmodernism, then of late capitalism itself."1

With that in mind, I’ve put together a list of cyberpunk classics in literature, film, TV and comics that continue to influence and shape the way I think about our future, or lack of it. More potent than the post-apocalypse, cyberpunk imagery and its themes predict a future that looks much like our current era, but even more precarious, authoritarian, surveilled and corporate-controlled. It’s the literature of those dispossessed by the dystopian present.

This is a long read. If you’re viewing it in email, it might be clipped. Click ‘View in browser’ (top right had corner) to read online.

No doubt my list contains a few you know already, perhaps I’ve missed something you consider even more important. I’ve merely skimmed the surface of a genre which has deep roots going back to the 1960s, and even further, so please jump in with your own recommendations in the comments. For those new to the genre, welcome. Jack in, turn on, zone out.

The Darkest Timeline: Living in a World with No Future

by Bram E. Gieben is out now from Revol Press.

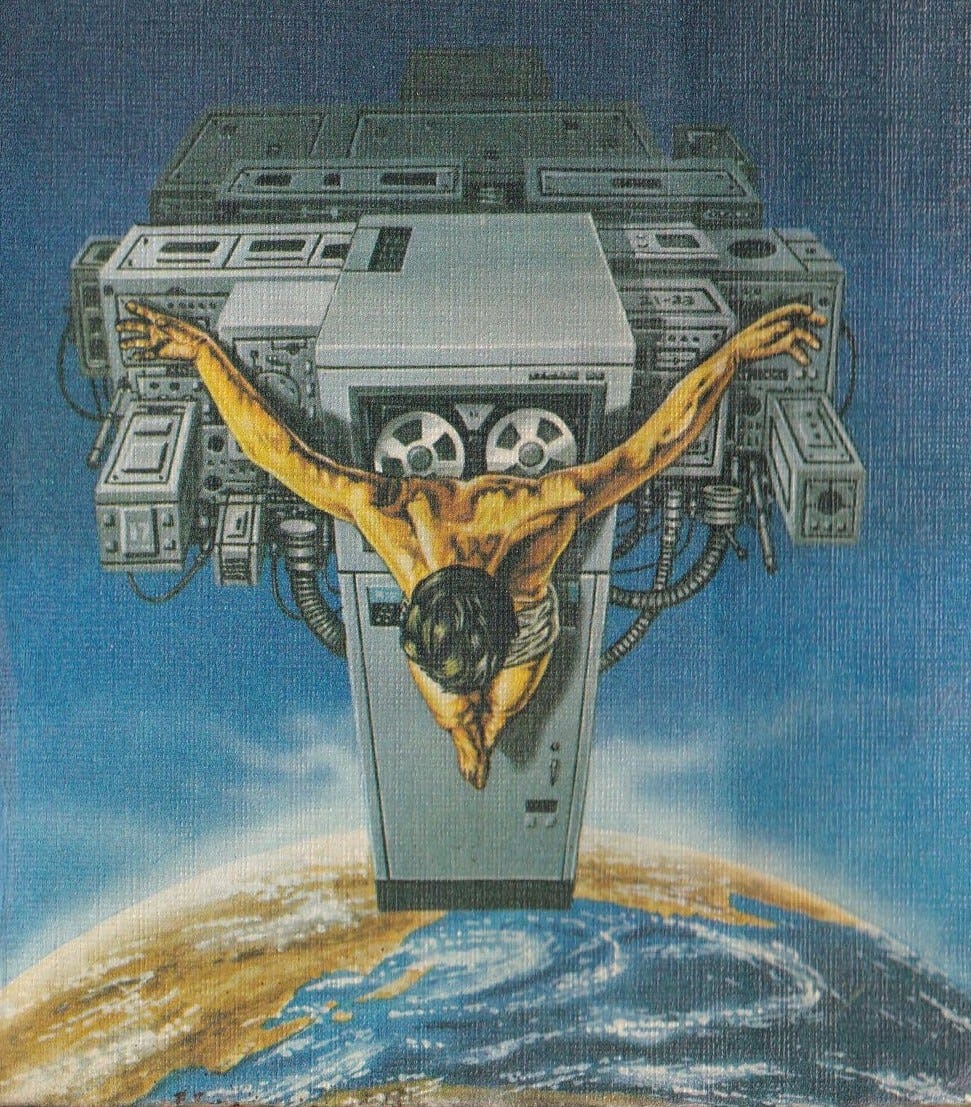

William Gibson: Neuromancer (1984)

Neuromancer is both William Gibson’s masterpiece, and in many ways the source text for all cyberpunk that follows it. Famously hand-typed on a 1950s model Hermes 2000 portable typewriter, the novel wears its influences on its sleeve. The aesthetic of 1982’s Blade Runner looms large in Gibson’s depiction of a futuristic Japan, and his worldbuilding owes as much to the sprawling 1960s science fiction epics of John Brunner as it does to the hard-bitten noir dialogue of Raymond Chandler detective stories. What captivated me as a young reader was the way Gibson captured the confluence of technology and human consciousness, and the corporate exploitation of both for profit. It was the perfect, cynical indictment of the politics of the Reaganaut, Thatcherite 1980s.

A recently commissioned TV adaptation, following years in development hell, promises to bring Gibson’s story of an alienated hacker who becomes entangled in a shadowy world of corporate espionage and malign artificial intelligence to a much wider audience. Neuromancer’s enduring influence might be its undoing in such an adaptation. It is a novel which has been expertly plundered for parts, influencing most if not all of the works mentioned in this post.

The muscular plot and prose belie a conceptually daring text, with ideas like the ‘consensual hallucination’ of cyberspace finding their first appearance in fiction in Gibson’s novel and related short stories. Its opening line is justly considered one of the greatest in science fiction and postmodern literature generally, and still contains the seeds of every single cyberpunk world-building project attempted since:

“The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel…”

Neal Stephenson: Snow Crash (1992)

By the time Neal Stephenson published Snow Crash in 1992, the cyberpunk genre was well-established, and ripe for parody. Stephenson turbo-charged the grimdark corporate world-building of the Gibson cyber-future with insane, cartoonish concepts like a Mafia-run pizza delivery firm, corporation-owned gated communities, and a limitless virtual world as the new crux of human culture, economics and ideology.

The novel’s finale involves a movement of rebel, stateless refugees led by a psychotic biker aboard a floating raft of trash attempting to take control of the metaverse using ancient Sumerian language. It’s a wild novel, its Looney Tunes tone perhaps best encapsulated by the name of its central character, the impossibly cool samurai delivery driver Hiro Protagonist.

Despite being rooted firmly in comedy and satire, Snow Crash has since proved just as prescient as the first-wave cyberpunk stories by Gibson and others, with Stephenson credited as being the first fiction writer to describe an online ‘metaverse’ peopled by ‘avatars’. This basic premise now underpins the technologies we call social media, and increasingly, video games - I wrote about this for Sublation Magazine last year.

Stephenson’s depictions of private communities, harried delivery drivers and atomised, self-employed gig workers is perhaps even more pertinent today. Also under development for TV, perhaps Snow Crash is easier to adapt than Neuromancer, if only because despite its wackiness, it looks a lot more like our present-day version of hypercapitalism.

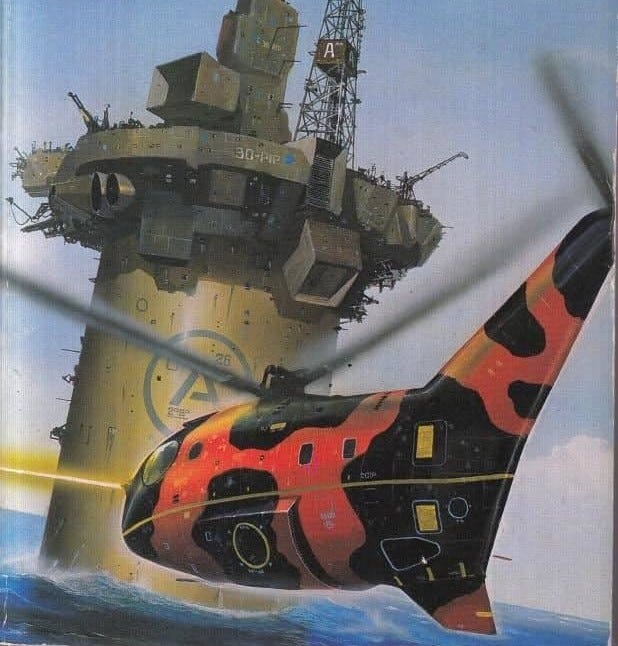

Bruce Sterling: Islands in the Net (1988)

A 1988 novel by Bruce Sterling, Islands in the Net is set exactly in our present moment, taking place between 2023 and 2025. Set in the world of corporate and government espionage, the rising political end economic powers are the ‘data havens’ in countries like Granada, Singapore and Switzerland, where the authorities turn a blind eye to piracy.

Like Kaleidoscope Century, Sterling’s novel is part of a tradition in cyberpunk that deals directly with history and politics. Examining the rise of a data-driven economy in the context of the fallout from the Cold War and the legacy of Western imperialism, Islands contains a ‘book within a book’ - The Lawrence Doctrine and Postindustrial Insurgency by Colonel Jonathan Gresham, a manual for political resistance against globalisation.

Like Neuromancer before it, Islands is a thriller. The plot is packed with James Bond-esque breathless action, riots, earthquakes, terrorists, spies and bomb plots. While entertaining us with all of this, Sterling delivers an uncannily accurate vision of the ‘Net’ as a site of corporate control and increasing political power, with data its capital. It’s a damning indictment of the global order’s ceding of political decision-making to corporations, and the devastating effects on the people this treats as collateral.

John Brunner: Stand on Zanzibar (1967)

It would be wrong to characterise John Brunner as a little-known or neglected author. Stand On Zanzibar was added to the SF Masterworks series in 2014, with the equally visionary The Shockwave Rider following it in 2020. It’s surely a matter of time until his classic of climate fiction, The Sheep Look Up, joins them. Nevertheless, Brunner was not an author I encountered while growing up, despite devouring as much as I could of his contemporaries, such as Philip K. Dick, J.G. Ballard and Poul Anderson. If anything, I encountered Brunner’s influence before I was aware of his existence. Both Zanzibar (first published in 1967) and Shockwave Rider (1975) explore many of the themes, approaches and concerns as first wave cyberpunk, and many authors including Gibson have cited Brunner as an influence.

In Zanzibar, Brunner depicted America dominating the world stage with the assistance of an intelligent supercompuer, Shalmaneser. Huge corporate entities vie for control as politicians grapple for influence over developing countries, while ignoring urban decay and sprawl in their own territories.

The plot plays second fiddle to the worldbuilding, as Brunner uses multiple intersecting first-person narratives and in-world media (in the form of TV broadcasts, newspaper articles, and fragments of songs) to depict a globally networked, dysfunctional society emerging into a new, technologically-dominated era. The effect is astonishing, and has been much imitated, not least in Warren Ellis’ cyberpunk comics masterpiece Transmetropolitan, and the penultimate season of the Westworld TV show.

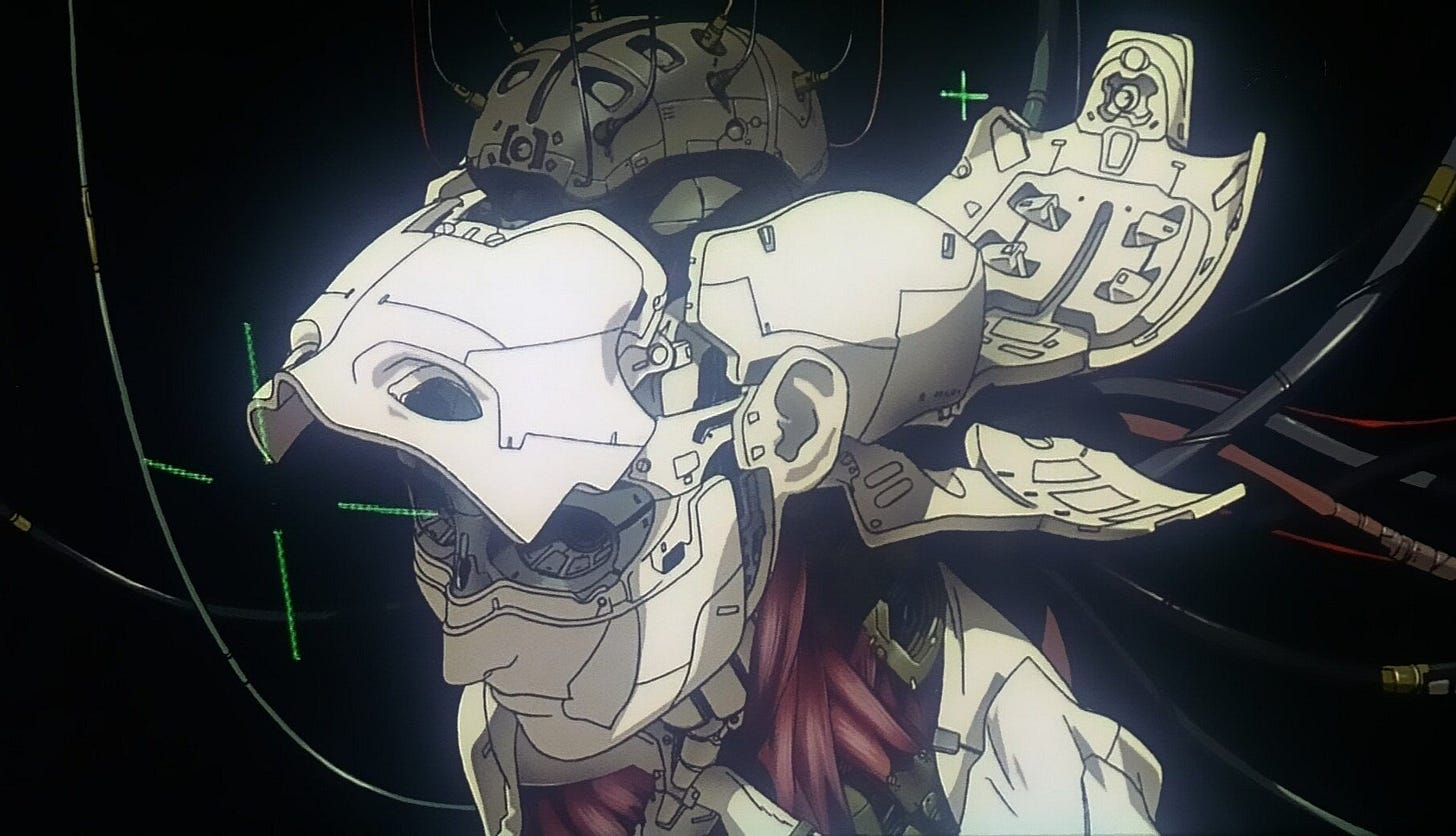

Mamoru Oshii: Ghost in the Shell (1995)

Another visual and thematic touchstone of the genre, Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell, like Neuromancer, was for a long time perhaps better known through its influence on Western media than as a cult manga in its own right. The story of Motoko Kusanagi, a cyborg law enforcement officer on the trail of a renegade hacker, is a nuanced and philosophically complex exploration of transhumanist themes, artificial intelligence, and human consciousness.

The 2017 film adaptation, while visually faithful, lost a lot in translation. Subsequent additions to the franchise have met with varying degrees of success both critical and creative, but the 1995 film arrives fully-formed, an instant classic that deserves its place alongside 1988’s ground-breaking Akira.

The original manga series began in 1989, just a few years after the Gibson-esque cyberpunk template began to influence the mainstream. It inarguably shares a place with Neuromancer as one of the iconic philosophical and visual source-documents of the genre, and feels as fresh and relevant today as it did three decades ago, with a few qualifiers.

Hideo Kojima, the visionary video game designer behind classics like Metal Gear Solid and Death Stranding, gave some thoughts on how the film and its themes have aged between its 1995 release and the 2017 Hollywood remake:

In 2017, one cannot simply whisper 'the net is vast and infinite' and hope for the impact such a statement had 22 years ago when it was uttered by Motoko Kusanagi to such great effect. In 1995, the internet was a mysterious, brave new frontier; today, it's a known quantity. Smartphones are glued to our hands, and we are constantly connected. For us, the net doesn't feel vast or infinite. In this modern world, then, where is the ghost of this latest Motoko Kusanagi to reside?2

Alex Rivera: Sleep Dealer (2008)

Alex Rivera’s bold, imaginative and ambitious 2008 Mexican cyberpunk film revolves around virtual reality and drone technology. In a world with closed borders, developed nations are still able to exploit low-wage labourers in less developed economies. Instead of immigrant workforces, in Rivera’s dystopian future the US relies on the efforts of workers remotely plugged into robot drones to power its expansion and construction. These workers endure punishing shifts, becoming so enmeshed with their robotic proxies that when a machine is damaged, the operator often dies in their haptic rig. This gives the anonymous virtual reality sweatshops Rivera depicts their name - sleep dealers.

Side plots explore the commodification of the lived experience of exploited workers for the benefit of middle-class audiences on social media, with confessional, sentimental ‘content’ consumed instead of news, and the brutal use of drones to suppress local populations in conflicts over water and resources. I write about Sleep Dealer in my book as an example of the value cyberpunk fiction can offer as an analytical tool. Rivera makes us confront not just the speculative consequences of our technological and sociological faith that progress will bring emancipation and freedom, but the harsh truth that we already live in a world of asymmetrical exploitation and discrimination. It’s an under-rated classic, and worth tracking down via Apple TV or on Blu-Ray.

John Barnes: Kaleidoscope Century (1995)

I’ve written about John Barnes’s visceral, incisive 1995 novel Kaleidoscope Century for the Strange Exiles blog (the essay appears in my book too). I also spoke about it with John himself in Episode 15. He agreed with my reading of it as a product of the Cold War politics Richard Hofstadter described in his 1964 Harpers essay, ‘The Paranoid Style’.

Barnes’ alternate history traces the life of an anonymous, amoral counterintelligence operative from the 1990s until the mid twenty-first century. The fallout from post-Cold War conflict culminates in a deadly confluence of military, industrial and networked technologies which present existential threats not just to human society and culture, but to the very notion of the individual human personality.

Influenced by Richard Dawkins’ theory of ‘memes’ as transmissible units of cultural information, Barnes outlines the awful truth that war and espionage drive technological innovation, and that the ultimate destination of progress may well be utter horror. It’s a brutal book in places, and not for those without a strong stomach, but it deserves recognition for its prescience and enduring relevance.

Richard K. Morgan: Altered Carbon (2002)

Some critics have argued that by the time Richard K. Morgan’s Altered Carbon was released in 2002, cyberpunk’s aesthetic template had become so well-worn that it was an empty set of tropes. In the cynical, reflexively violent worldview of the protagonist Takeshi Kovacs, there is no doubt something of the archetype established in Neuromancer’s alienated hacker Case, and Blade Runner’s disaffected cop Rick Deckard.

An enhanced military specialist, Kovacs is pressganged into working as a private detective, and the novel owes its structure as well as its prose style to the classic detective novels that influenced Gibson. Despite its familiar palette, themes, style and prose, Altered Carbon is nonetheless an almost flawless execution of the genre, with enough original ideas contained in it to more than earn its place in the pantheon of cyberpunk classics.

Elements such as the artificially intelligent (and superbly well-armed) hotel where Kovacs sets up his base of operations, and the weaving strands of political, military, and seedy, street-level corruption are executed masterfully, but it is Morgan’s central concern that elevates the novel to classic status. In this techno-saturated future, rich members of the elite can be ‘re-sleeved’ in new bodies, making them effectively immortal.

This immunity from the stakes and needs of the vast swath of humanity that cannot afford the technology makes the ‘Meth’ (Methuselah) class sublimely indifferent to human morals, concerns, and bodies. It’s a sharp metaphor for the inequality that sustains our present-day class of parasitic billionaires; an economic caste who consider human lives unimportant, and human bodies expendable.

Morgan outlines this vicious calculation in a memorable speech by his villainess Kawahara that perfectly encapsulates the worldview of many cyberpunk antagonists:

“The value of a human life." Kawahara shook her head like a teacher with an exasperating student. "You are still young and stupid. Human life has no value. Haven't you learned that yet, Takeshi, with all you've seen? It has no value, intrinsic to itself. Machines cost money to build. Raw materials cost money to extract. But people?" She made a tiny spitting sound. "You can always get more people. They reproduce like cancer cells, whether you want them to or not. They are abundant, Takeshi. Why should they be valuable?”3

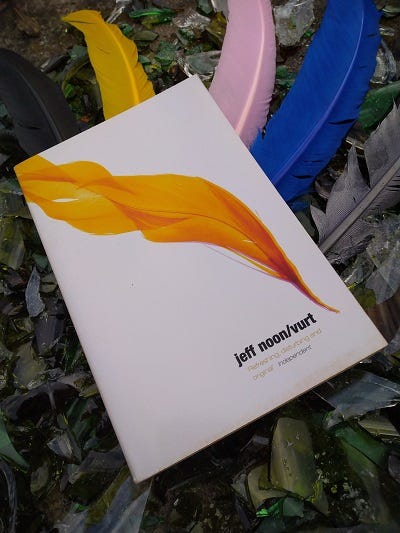

Jeff Noon: Vurt (1993)

I first encountered Jeff Noon’s writing, fittingly, in the environs of an afterparty following an illegal rave. A friend and I talked about science fiction until the sun came up and the drugs wore off, and I went straight to the bookshop to buy a copy of Vurt.

Noon’s hallucinatory prose and labyrinthine, often mind-bending plots offered a very British take on our emerging cyber-history’s more dystopian aspects, and likely destination. Suffused with neologistic language and drugs, psychedelic technologies and dreamlike logic, his books have as much in common with the experimental fictions and thought experiments of Lewis Carroll and Jorge Luis Borges as they do with conventional cyberpunk.

Vurt was his debut, a visionary tale of a near-future Manchester where a shared alternate reality can be accessed through the consumption of psychedelic feathers, which act as a gateway to this shared virtual, consensual hallucination. In Vurt, the integration of technology with human consciousness and our physical bodies delivers a world of addiction, chaos and authoritarian capitalism run amuck, one that can only be escaped by flight into virtual worlds.

If Philip K. Dick has an heir, it’s Noon, a true master of the ‘reality slip’ and the high-concept drug. Later novels like Needle in the Groove would channel the technologically-augmented music and explicit hedonism of 90s underground dance culture even more directly, securing Noon’s place as the science fiction laureate of the rave generation.

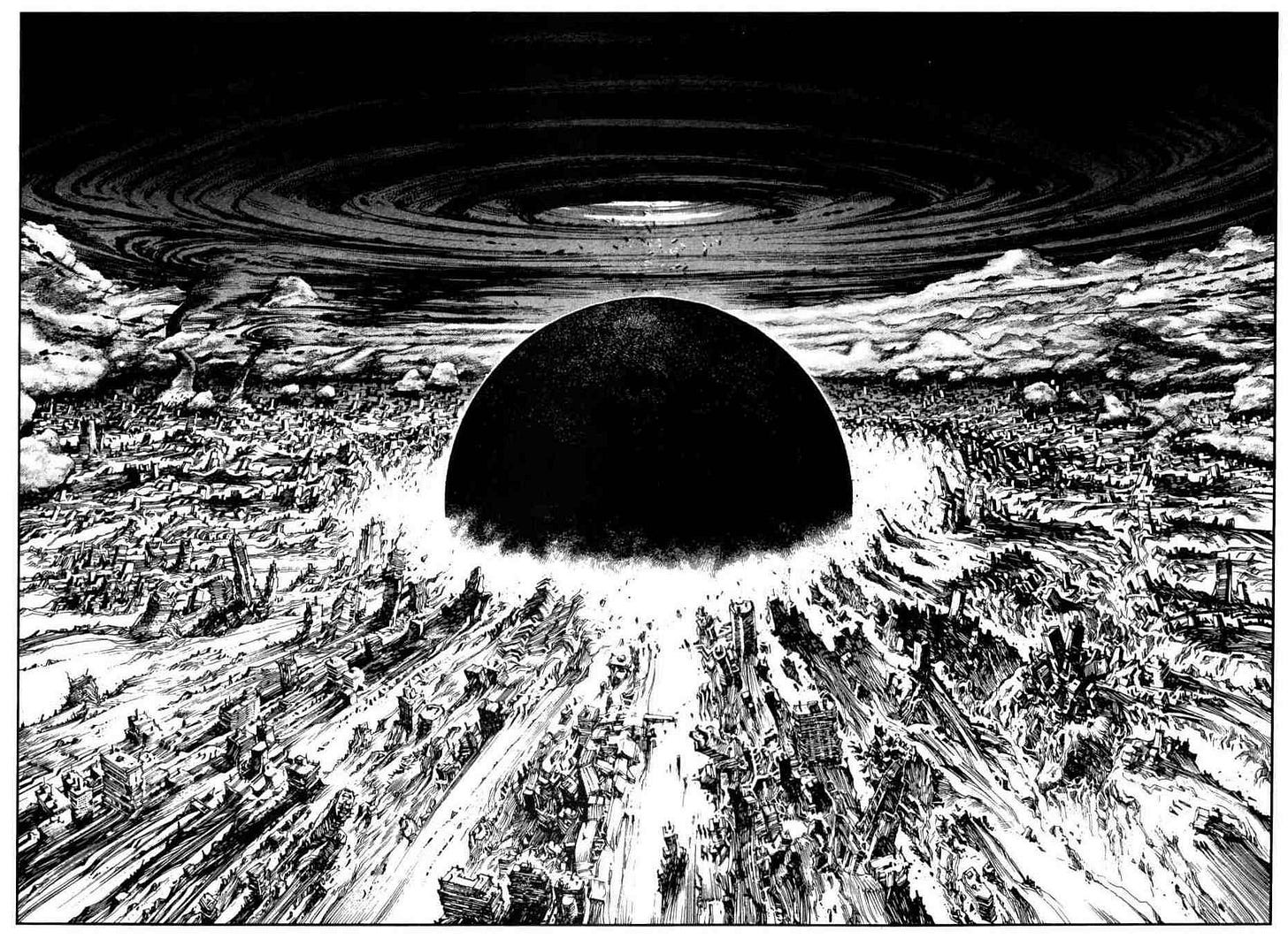

Katsuhiro Otomo: Akira (1982)

Best known through its 1988 animated adaptation, Akira deserves equal consideration as a cyberpunk source text as Neuromancer. The film distills the themes, characters and imagery of the original manga into an elliptical, haunting and strange coming of age tale, with a conclusion that leaves many of the philosophical questions it explores unanswered. The original comic, which ran from 1982 to 1990, is a much more vast and sprawling text.

Given thousands of pages to breathe, each plot and character is given more space to develop. Themes the film barely touches on, like the gangs who emerge and vie for control in the wake of the ‘Akira event’ in the ruins of Neo Tokyo, are explored and unpacked in an epic tale that pays homage to the samurai films of Akira Kurosawa and Toho’s classic kaiju movies, along with the prototypical cyberpunk aesthetics of Blade Runner.

Katsuhiro Otomo’s precise visual style delivers the story with a documentarian’s commitment to realism that chillingly conveys science fiction allegories for the inescapable, apocalyptic effects of the Nagasaki blast (see panel, above), and its historical aftermath. Notably, the aftermath is as important as the event itself, as Otomo told Kodansha Comics in 2019:

Certainly, destruction and rebuilding are depicted in my works, Akira in particular. In Akira the apocalypse happens in the midpoint of the story, so I think you can understand how much I’m interested in the two sides of what you call the “utopia within the apocalypse.”4

Like Ghost in the Shell, both the manga and its adaptation have some nuanced questions to ask about human consciousness, and the value of human life. It would be an error to call the film a poor adaptation - it’s an opaque, somewhat psychedelic take on the source material, and no less impressive an achievement in its iconic visual world-building and painstaking, frame-by-frame animation.

While the lack of plot points about cyberspace, virtual reality, cyborgs or hackers make Akira an odd fit for the cyberpunk genre, its influence on cyberpunk creators that followed it cannot be overstated. It is a visual and aesthetic lodestone of the genre, similar to Blade Runner, and like Ridley Scott’s film, it shares with cyberpunk some deep meditations on being, transhumanism, and the evolution of the human species.

It remains to be seen whether a promised film adaptation from Taika Waititi, long stuck in development hell, can avoid the Hollywood GiTS trap of emptying out the symbolic contents of the artwork in order to make an empty but impressive visual spectacle. To truly appreciate the reasons for Akira’s enduring influence and originality, spend your money on the books first.

John Wagner & Carlos Ezquerra: Judge Dredd (1979)

The most successful and enduring character in British comics history is not Dan Dare, the heroic ‘pilot of the future’ inspired by the plucky airmen of the Battle of Britain. By the late 1970s, Dare looked not just hopelessly outdated, he had also become emblematic of a declining and problematic British Empire. Heroes like Dare no longer spoke to a young comics readership living in the increasingly dystopian inner cities of 70s Britain.

Enter Judge Dredd, conceived by creators John Wagner and Carlos Ezquerra as a satirical grotesque, a caricature of the ultimate fascist cop. With his catchphrase, “I am the law,” Dredd first brought his unique brand of violent justice to the streets of Mega City One in 1977, in the first issue of 2000AD.

While Dredd himself would go on to become so popular that he lost some of his satirical bite, becoming less and less of an anti-hero, the environs of Mega City One remain one of the deepest wells of inspiration for subsequent cyberpunk dystopias. From the towering apartment blocs housing tens of thousands of people, to the streets choked with mutated psychos and criminal tweakers, the writers and artists who inherited the city from Wagner and Ezquerra have built it into perhaps the most enduring backdrop ever created for cyberpunk stories. Its staying power lies in its adaptability; its utility as a metaphor-engine for stories about the poverty, overcrowding, violence and social dislocation that still plague cities consumed by inequality and runaway elitism.

John Brunner: The Shockwave Rider (1975)

John Brunner’s 1975 classic has nearly every single notable feature of the cyberpunk blueprint, just a decade early. Its protagonist is a constantly self-reinventing computer hacker who uses his skills to evade the shadowy, authoritarian and corporate forces controlling the dystopian America Brunner depicts.

The plot revolves in part around a ‘futures market’ for world events, news and even identities called the Delphi Pool. Through networked computer communication, America has become a panopticon state, with every citizen’s move surveilled. Fortunes are made and lost using the data this generates. Brunner uncannily predicts a world where the value of aggregated data about human behaviour is of more use for profit and control than direct dominance. In such a world, only a hacker can be free.

Like the early ‘phone phreakers’5 (considered prototypical hackers), our hero can control computer systems using public telephones (remember them?). As he runs from the Akira-like Tarnover organisation, dedicated to finding and controlling gifted children, he moves through a world of street gangs, Zaibatsu-style ‘hypercorps’, student rebels and technological refuseniks.

The novel has often been cited for its early description of a computer ‘worm’ (virus), but its depiction of an atomised world of surveilled individuals lost in a shifting sea of real and assumed identities now seems its most prescient conceptual leap.

Shinya Tsukamoto: Tetsuo II: Body Hammer (1992)

Shinya Tsukamoto’s first entry in the Tetsuo series was a hymn to the fusion of human and machine through sexual excitement, a body-horror death trip that drew on J.G. Ballard’s Crash and the sexualised flesh-rending of early David Cronenberg. Its sequel is a different beast.

Where Iron Man’s protagonist finds himself fusing with machine parts following a hit and run accident, the anti-hero of Body Hammer transforms into a literal weapon to seek justice after his son is murdered. What follows is one of the purest visual expressions of the cyberpunk concern with man-machine co-evolution ever committed to film.

Like the first film, the action plays out in a dreamlike way. What we are witnessing is not a classical science fiction allegory, with some point to make about the social costs or the philosophical ramifications of fusing flesh with metal, and mind with simulation. Rather, it feels like the graphic and disturbing fulfilment of a taboo fetish or fantasy, wrenched from the near future. Cyberpunk has rarely been nastier, sexier, or more difficult to watch.

Charles Stross: Accelerando (2005)

Charles Stross has turned his hand to hard science fiction, space opera, Lovecraftian horror, supernatural mystery and every other genre you could think of since his 1987 debut in Interzone, but it was his propulsive, wickedly funny Accelerando that first caught my attention. Built from interconnected strands of family history taking place before, during and after a technological singularity, Stross’s vision of the near future explores rogue artificial intelligence, self-replicating nanotechnology and uploaded consciousness.

Beginning in a future so near it was imminent even at the time of the novel’s publication, the action explodes forward in time, tracing the inevitable consequences of liberating human minds from their physical bodies. Personalities, generations, and the story of human life itself begin to become entangled over such vast expanses of time and distance. Rather than freeing humanity from an oppressive capitalist paradigm, life-extension and almost boundless space travel merely open up more opportunities for economic, cultural and personal conflicts.

In tracing the line from a cyberpunk near-now to a distant, space opera future, Stross attempts something bold. He successfully marries the concerns of traditional science fiction with more immanent anxieties about the technological maelstrom of the singularity, which is cyberpunk’s stock in trade. It feels apt to end this list with a book where the horizon of the future is not delimited by absolute apocalypse, or inevitable technological horror. Instead, we get to find out what happens to the descendants of the first generations to interact with AI, transhumanist technologies, data-driven capitalism, and eventually, Dyson spheres and faster than light space travel. In Stross’s cyberpunk future, we all get to live forever. Even the cat.

The Darkest Timeline: Living in a World with No Future

by Bram E. Gieben is out now from Revol Press

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, p. 419

Morgan, Richard K., Altered Carbon, Gollancz, 2008, p524.

Otomo, Katsuhiro, interviewed in 10 Years of Kodansha Comics

This 2012 Atlantic article offers a nice history of phone phreaking, an early form of computer hacking done via landline phones.

Thanks for so many interesting recommendations, I'm currently reading Kaleidoscope Century and it's a brilliant book so far. Have you seen Upgrade (2018)? I really like that film, it's a very engaging watch

It's not cyberpunk, but I am curious if you ever read Mockingbird by Walter Tevis. Incredibly prescient.